Travels in the Southwest: March & April, 2023 (#2)

Section #2

(Too much fun for just one blog post)

Theme #2: Birds

One of the things I love most about birding is how it shifts your perceptions, adding layers of meaning and brokering connections — between sounds and seasons, across far-flung places and between who we are as people and a wild world that both transcends and embraces us.

Christian Cooper

White-winged Dove

Male Acorn Woodpecker

Juvenile female Broad-tailed Hummingbird

Violet-crowned Hummingbird

Curve-billed Thrasher

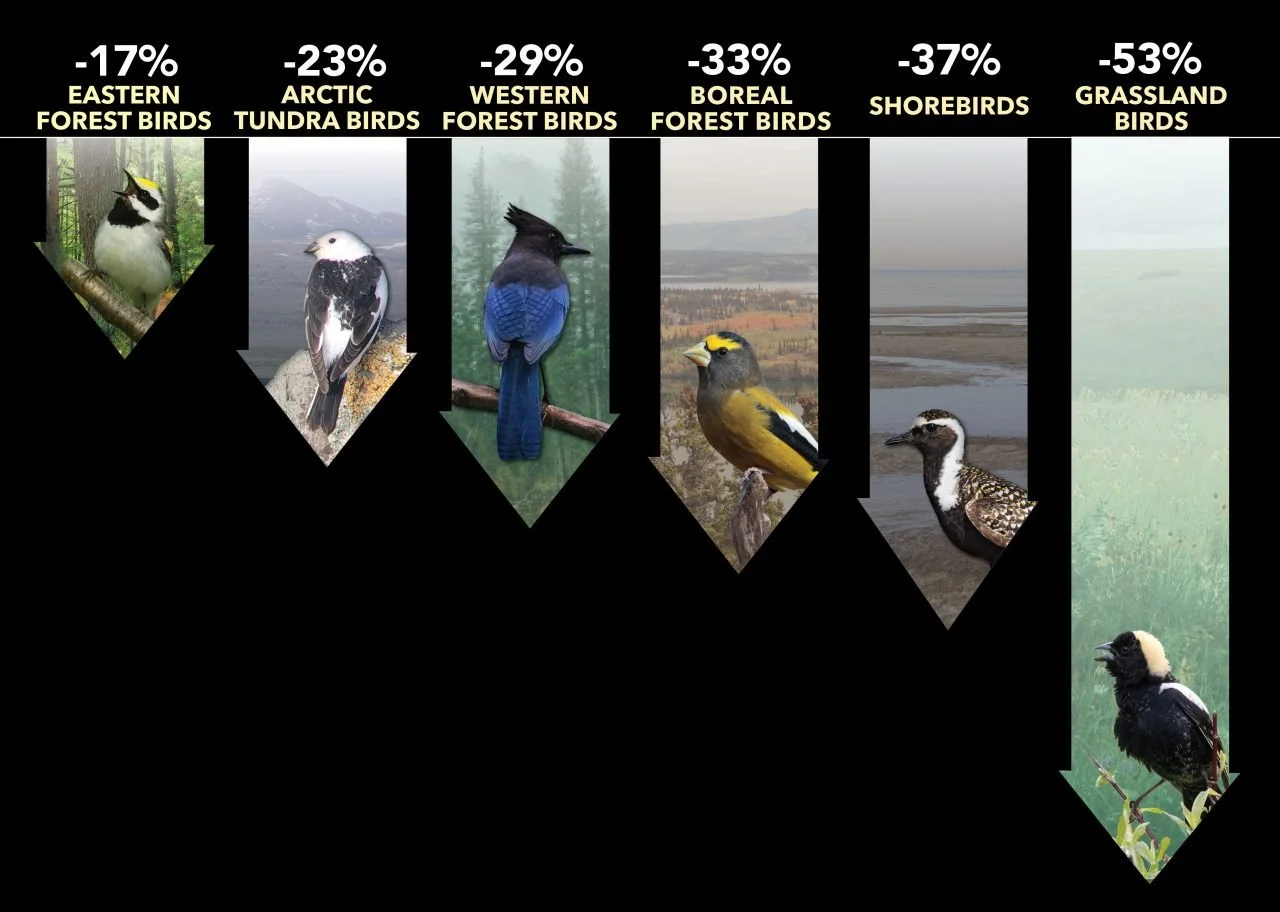

The Full Picture: A Climate and Ecological Crisis

“These are systems and biomes in serious trouble. I think we need to approach conservation of these endangered systems at a much more holistic level.” KV Rosenburg

KV Rosenburg, et al. Science. 19 Sep 2019, Vol 366, Issue 6461, pp. 120-124

Slowing the loss of biodiversity is one of the defining environmental challenges of the 21st century. Habitat loss, climate change, unregulated harvest, and other forms of human-caused mortality have contributed to a thousandfold increase in global extinctions in the Anthropocene compared to the presumed prehuman background rate, with profound effects on ecosystem functioning and services.

The overwhelming focus on species extinctions, however, has underestimated the extent and consequences of biotic change, by ignoring the loss of abundance within still-common species and in aggregate across large species assemblages. Declines in abundance can degrade ecosystem integrity, reducing vital ecological, evolutionary, economic, and social services that organisms provide to their environment.

Birds are excellent indicators of environmental health and ecosystem integrity, and our ability to monitor many species over vast spatial scales far exceeds that of any other animal group. In 2019, Rosenberg et al. reported wide-spread population declines of birds over the past half-century, resulting in a net loss approaching 3 billion breeding birds, or 29% of 1970 abundance across a wide range of species and habitats. Declines are not restricted to rare and threatened species—those once considered common and wide-spread are also diminished.

This loss of bird abundance signals an urgent need to address threats to avert future avifaunal collapse and associated loss of ecosystem integrity, function, and services. The findings have major implications for conservation of wildlife more broadly, and policies associated with the protection of birds and native ecosystems on which they depend.

Huachuca Mountains: Arizona

The Huachuca Mountains, with Miller Peak (9,466 feet) being the tallest summit, are the third highest of southeastern Arizona’s Sky Island ranges. Top elevations support mixed conifer forests on north-facing slopes while pines nestle in the more southerly aspects. Lower zones have extensive oak and oak-pine woodlands.

The riverine stretches are delightful. Spring-fed streams, northeast orientation, and high ravine walls provide the east-side Huachuca canyons with a moist cool environment unusual in the desert southwest. Water-loving trees like sycamores and maples grow along the river’s banks, often within a few feet of cacti, yucca, and agaves.

Huachuca’s diverse habitats support some of the best birding in Arizona . Summer avian residents include at least 14 species of hummingbirds, Elegant Trogon, Dusky-capped and Sulphur-bellied Flycatchers, Plumbeous Vireo, Painted Redstart, Hepatic Tanager, Scott’s Oriole and many more “special” birds.

Scott’s Oriole: male (left) and female (right)

Ramsey Canyon

We visited Ramsey and Ash Canyons, lodging at an Inn situated adjacent to the entrance of Ramsey Canyon. The Nature Conservancy manages Ramsey Canyon as a Preserve and seems to do a decent job. One can meander along gentle trails within the riverine area, but also have the option of ascending the canyon’s steep slopes via the Hamburg trail and venturing beyond into Miller Peak Wilderness.

John James built this creek-side house in 1911 when his 1902 cabin (further upstream) became too small for the family.

Ramsey Canyon Leopard Frog (Rana subaquavocalis)

Ramsey Canyon Preserve manages an artificial pond that provides refuge for a leopard frog that was federally listed on July 16, 2002 as an Endangered Species. As suggested by its scientific name, this is one of the few frog species that sings underwater. However, the lovely latin name has gone. DNA typing demonstrated that the Ramsey Canyon Leopard Frog is indistinguishable from the southern population of the Chiricahua leopard frog (Rana chiricahuensis). The Chiricahua leopard frog is mostly aquatic and generally restricted to perennial waters, but can disperse overland and along drainages during summer monsoons.

Chiricahua leopard frogs once occupied a variety of wetland habitats throughout south-central Arizona, west-central New Mexico and into Mexico. They has been extirpated from over 80% of historical U.S. localities and the remaining populations are small and scattered.

The species faces four primary threats:

Habitat loss is the main problem. Development, water diversions, groundwater pumping, grazing, environmental contamination, etc. are increasing throughout leopard frog habitat.

Introduced species such as bullfrogs, crayfish and non-native fishes pose danger from predation and food competition.

A fungal skin disease called chytridomycosis is killing frogs, toads, and salamanders worldwide. The disease causes lethargy, abnormal posture, loss of the righting reflex, and death.

Climate change is expected to increase drought conditions in USA southwest and eliminate already rare habitat.

(Photo by Jim Rorabaugh, USFWS)

Flocks of birders

Huachuca’s canyons are chock-full with birders - many casual, some extremely accomplished. A common greeting is “Have you seen the Trogon?”. Only a few have.

Long lenses abound, everyone moves in a strange stealth-like way, pausing periodically to raise binoculars and peer intently into the tree canopy.

Bird feeders are maintained at many sites and a few blinds are available. Several species are regular visitors to feeding stations. But the wildlife are not the only ones searching for a tasty morsel. We confess (without guilt) that our birding endeavors halted for a while at 4 o’clock every afternoon, when the Inn provided delicious pies to guests.

Top row: Left - Mexican Jay; Right - Wild Turkey at Ramsey Canyon Inn feeders

Bottom row: Left - Chipmunk spp.; Right - Javelina (Collared Pecary)

Ash Canyon

Tim Blount is the resident ornithologist at Ash Canyon Bird Sanctuary and is very helpful and welcoming. Although peak hummingbird season is mid-summer, during our time at the Huachuca Mountains we saw plenty of frenetic action from six species of these amazing birds.

Male Anna’s Hummingbird

1st row: Left - Male Acorn Woodpecker; Right - Female Broad-tailed Hummingbird.

2nd row: Left - Male Cassin’s Finch; Right - White-winged Dove.

3rd row: Left - Chipping Sparrow; Right - Adult Mexican Jay.

4th row: Left - Pine Siskin; Right - Male Lazuli Bunting.

Male adult Rivoli’s Hummingbird.

Rivoli’s Hummingbird (Eugenes fulgens)

Distribution:

Rivoli's Hummingbird was named in honor of Francois Victor Massena, the Duke of Rivoli when the species was described by René Lesson in 1829. It is the second-largest hummingbird species in the United States and is found from the southwestern United States to northern Nicaragua. Birds migrate north in early spring to breed in mountains of southeastern Arizona, extreme southwestern New Mexico, and possibly in the highlands of northern New Mexico.

Rivoli’s Hummingbird is locally common in Sonoran Madrean pine–oak zones, at elevations from 1,600 to 2,700 m. Individuals descend to lower canyon feeding stations, among evergreen oaks and sycamores, but nest during April at higher elevations in canyons and conifer-dominated slopes. The species exhibit strong philopatry (the tendency to return to the area of the one’s birth). Birds typically leave the U.S. in late September or early October but a few may stay in USA for the winter.

Male juvenile Rivoli’s Hummingbird.

Feeding:

Rivoli’s Hummingbirds consume floral nectar from several plant species and catch small insects in the air or gleans them from foliage. Preferred nectars contain primarily sucrose and low quantities of other substances such as amino acids. Individuals can discriminate among nectars of different sugar concentrations and may use color as a cue to target flowers with higher concentration.

Traplining is a feeding strategy in which an animal visits food sources on a regular, repeatable sequence, much as trappers check their lines of traps. It is usually seen in species that forage for plant resources, such as bees, butterflies, bats, hummingbirds and fruit-eating mammals. Traplining hummingbirds utilize a specified route that the individual traverses in the same order repeatedly to check specific plants for flowers that hold nectar. The evolution of traplining in hummingbirds is thought to entail morphological specialization through the reciprocal coevolution of longer bills with the long-tubed flowers of widely dispersed plant species. Based on measured feeding rates of captive Rivoli's Hummingbirds from the Chiricahua Mountains, it appears that free-living Rivoli’s are trapliners and consume frequent small meals that reduce flight costs and competition for food.

Physiology:

Hummingbirds have high metabolic rates and maintain their body temperatures at about 40°C. Rivoli’s Hummingbirds hover at about 22 beats/s and, when hovering, increase their energy output to 11x their basal metabolic rate. The high metabolic requirement of Rivoli's Hummingbird is consistent with the fact that it has one of the highest recorded heart rates of any vertebrate (range 420–1,200 beats/min). This does not differ substantially from that of other hummingbirds, even those of smaller size, indicating that the heart of a Rivoli's Hummingbird may be working at maximum capacity for its cardiac system.

Female adult Rivoli’s Hummingbird.

Hypothermic torpor:

Rivoli's Hummingbird can enter torpor at night to reducing nighttime energy expenditure but will avoid torpor when energy intake is high. It appears the birds enter torpor about half the time. Torpor is undertaken even at relatively warm temperatures (< 30°C) and is regularly used when total body fat falls below 4%. Steady-state oxygen consumption of torpid birds decreases with temperature in an exponential fashion. When ambient temperature drops below 14°C, oxygen consumption increases, presumably to defend some minimum body temperature.

Male adult Rivoli’s Hummingbird.

Behavior:

Males are highly territorial in southern parts of their range. Dominance is a function of body size; male Rivoli's Hummingbird is able to intrude uncontested into territories of smaller species and successfully exclude other hummingbirds from their own territories. In USA, Rivoli Hummingbirds males are typically subordinate to male Blue-throated Hummingbirds which can result in their need to use poor-quality food sources.

In southeastern Arizona, individuals are less territorial because they trapline and do not seem to be tied to any nectar source.

Male adult Rivoli’s Hummingbird.

Nesting:

In southeastern Arizona nests are open cup of soft downy feathers and mosses, with an exterior that is liberally covered with lichen. Eggs are laid in May - usually 2 white, smooth-surfaced, oval eggs. Only the female is known to incubate; hatchlings are altricial (helpless and requiring significant parental care).

Nestling survival has been studied at Rucker Canyon in the western Chiricahua Mountains. 68% of all hummingbird nest mortality resulted from depredation, probably snakes and avian predators such as Mexican Jay, Hooded Oriole and Summer Tanager. Some Rivoli’s Hummingbird adults are known to have lived for 11 years.

Male adult Rivoli’s Hummingbird.

Conservation:

The population size is considered large (<10,000 mature individuals) and the population trend is one of increase. The species is of Least Concern globally. Feeders offer an energy subsidy that can maintain unnaturally large populations in certain areas when natural food flowers are scarce (e.g., Chiricahua & Huachuca Mountains, where many flowers do not bloom until the onset of monsoon rains in July). Because the range of the Rivoli's Hummingbird within the U.S. is restricted to higher elevations of small isolated mountain ranges, forest fires can severely restrict habitat availability over the short term. Habitat destruction in southern Mexico and Central America may have a longer-lasting impact on populations. (Information from The Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.)

1st row: Left - Male Anna’s Hummingbird; Right - Female Anna’s Hummingbird.

2nd row: Left - Male Black-chinned Hummingbird; Right - Female Black-chinned Hummingbird.

3rd row: Left - Male Broad-billed Hummingbird; Right - Yellow-rumped Warbler.

4th row: Left - Female Broad-billed Hummingbird; Right - Male Broad-tailed Hummingbird.

5th row: Left - Male House Finch; Right - Female House Finch.

6th row: Left - Male Ladder-backed Woodpecker; Right - Male Brown-headed Cowbird.

7th row: Left - Male House Finch with deformed beak - heaven knows how it survives!; Right - Male Lesser Goldfinch.

8th row: Left - Male Rufous Hummingbird; Right - Violet-crowned Hummingbird.

9th row: Left - Yellow-rumped Warbler; Right - Lucy’s Warbler.

10th row: Left - Curve-billed Thrasher; Right - Wild Turkey.

Male Black-chinned Hummingbird

Whitewater Draw, Arizona

The Whitewater Draw Wildlife Area in southern Sulphur Springs Valley is managed by Arizona Game and Fish. The region is classified as Chihuahuan desert grassland. Previously the land was farmed but much of it is being returned to native grassland through reseeding projects. Some sections are intentionally flooded during winter months to sustain waterfowl and rare species such as the plains leopard frog.

Whitewater Draw marshlands

Dawn light washing over the Draw

Waterbirds

Whitewater Draw is the primary wintering area for about 30,000 Sandhill Cranes from both the Rocky Mountain and Mid-Continental populations. Lesser (more numerous) and Greater subspecies are present. The former breed in Alaska and Siberia, the latter in northern US.

We saw about a dozen cranes in the distance; most of their colleagues had already migrated north. A sizable flock of Snow and Ross’ Geese remained, the birds resting at the marshes.

Mixed flock of Snow Geese and Ross’s Geese

While we were watching, the geese took flight, spreading out to forage in neighboring farmlands.

Whitewater Draw’s wetlands attract a variety of other water-associated and grassland birds. We were lucky enough to see a few species during our short stay.

The most serious conservation issue for Whitewater Draw is increased drought and diminished seasonal winter flooded wetland due to climate change. This threat is particularly relevant for the inter-mountain West.

1st row: Left - Male Northern Shoveler; Right - Female Northern Shoveler.

2nd row: Left - Immature White-crowned Sparrow; Right - American Coot.

3rd row: Left - Cooper’s Hawk; Right - White-faced Ibis.

Campsite

Not the most romantic camp of our trip.

But it provided easy access to the Draw and the wind was in our favor.