Travels in the Southwest: March & April, 2023 (#1)

Section #1

(Too much fun for just one blog post)

The Invitation

Email November, 2022:

“We have made reservations for Big Bend next spring. Maybe you could join us?” - From B. & T. who live in Tennessee.

Who can resist such an invitation, especially when we learnt that E. & C. from Florida would join the team. This was going to be a blast!

We drew up a 2-month itinerary which was really nothing more than a “wish list”.

Cactus Wren on saguaro

The Full Picture: A Climate and Ecological Crisis

“This is the biggest story in the world, and it must be spoken as far and wide as our voices can carry, and much further still.”

Greta Thunberg: The Climate Book. Penguin Press, NY, 2023

Left: Looking west from Alamo Camp at Venus and a waxing moon, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

Right: Saguaro in morning light at Kofa National Wildlife Refuge.

Let’s get out of here!

The tricky bit was timing our departure – California was being thrashed incessantly by a series of violent storms.

Atmospheric rivers are described as long, flowing regions of the atmosphere that carry water vapor through the sky. They are about 250 to 375 miles wide and can be more than 1,000 miles long. The heavy precipitation, which can park over a region for several days, can lead to flooding, mudslides and other disasters.

On February 27th, during a lull between two storm fronts, we made the dash over Tehachapi Pass, California.

Just Another Day

Our journey is chronicled around several concepts or themes.

Theme #1: Wilderness

Twilight in the Sonoran Desert

Top: Creosote flower

Bottom: Prickly Pear (Opuntia species)

Kofa National Wildlife Refuge, Arizona

Wilderness is a nebulous characteristic, more of a feeling than a place. For me, born in Africa, it suggests unfettered nature, Darwinian rules, personal insignificance and an opportunity for internal peace.

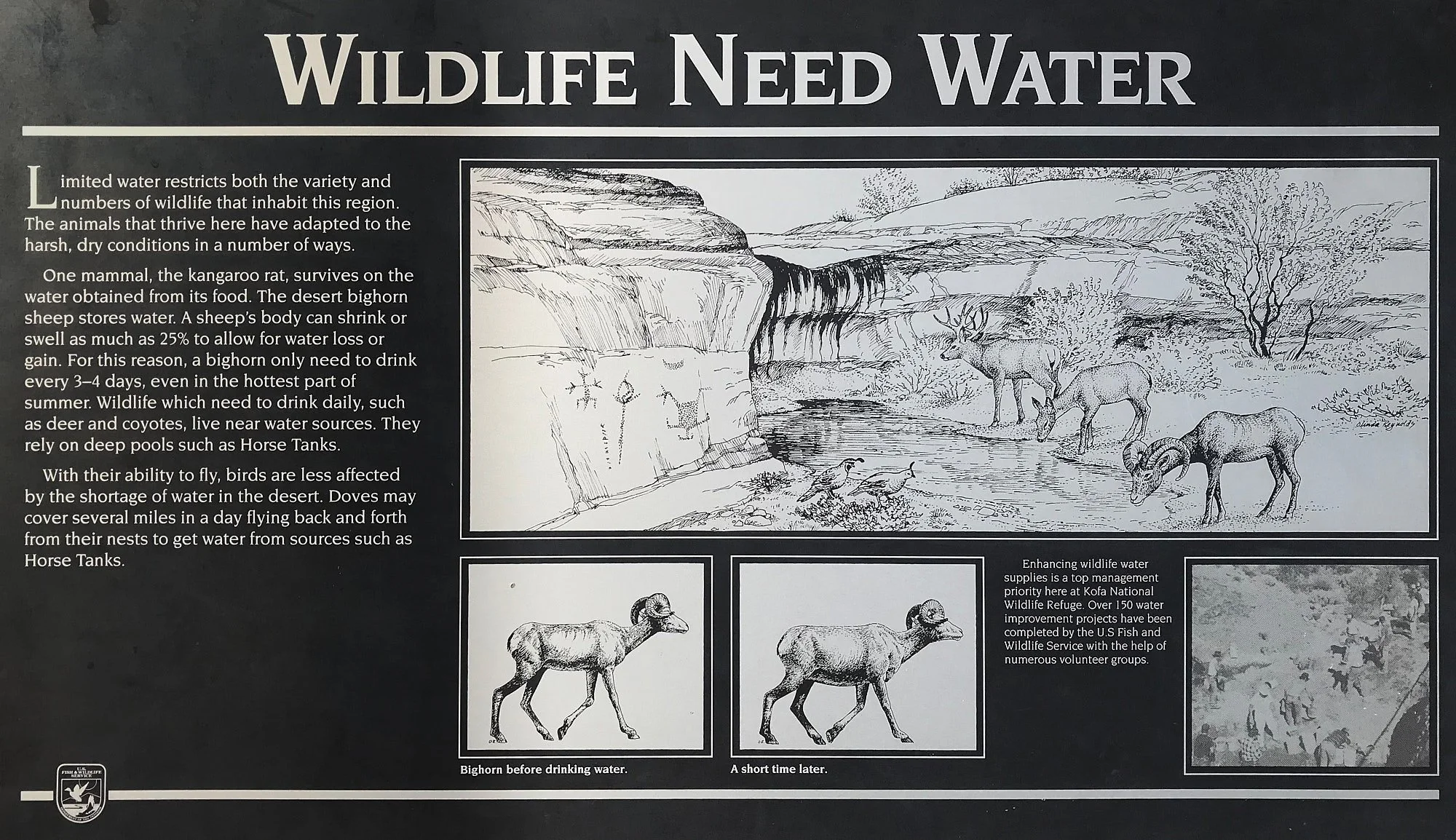

Kofa is such a place. It lies within the hot, dry, Lower Colorado subdivision of the Sonoran Desert and was established in 1939 for the protection of desert bighorn sheep and other native wildlife.

Looking northeast (top image) and north (bottom image) from Horse Tanks. Note the wide separation of individual plants - a botanical survival strategy in the harsh desert environment.

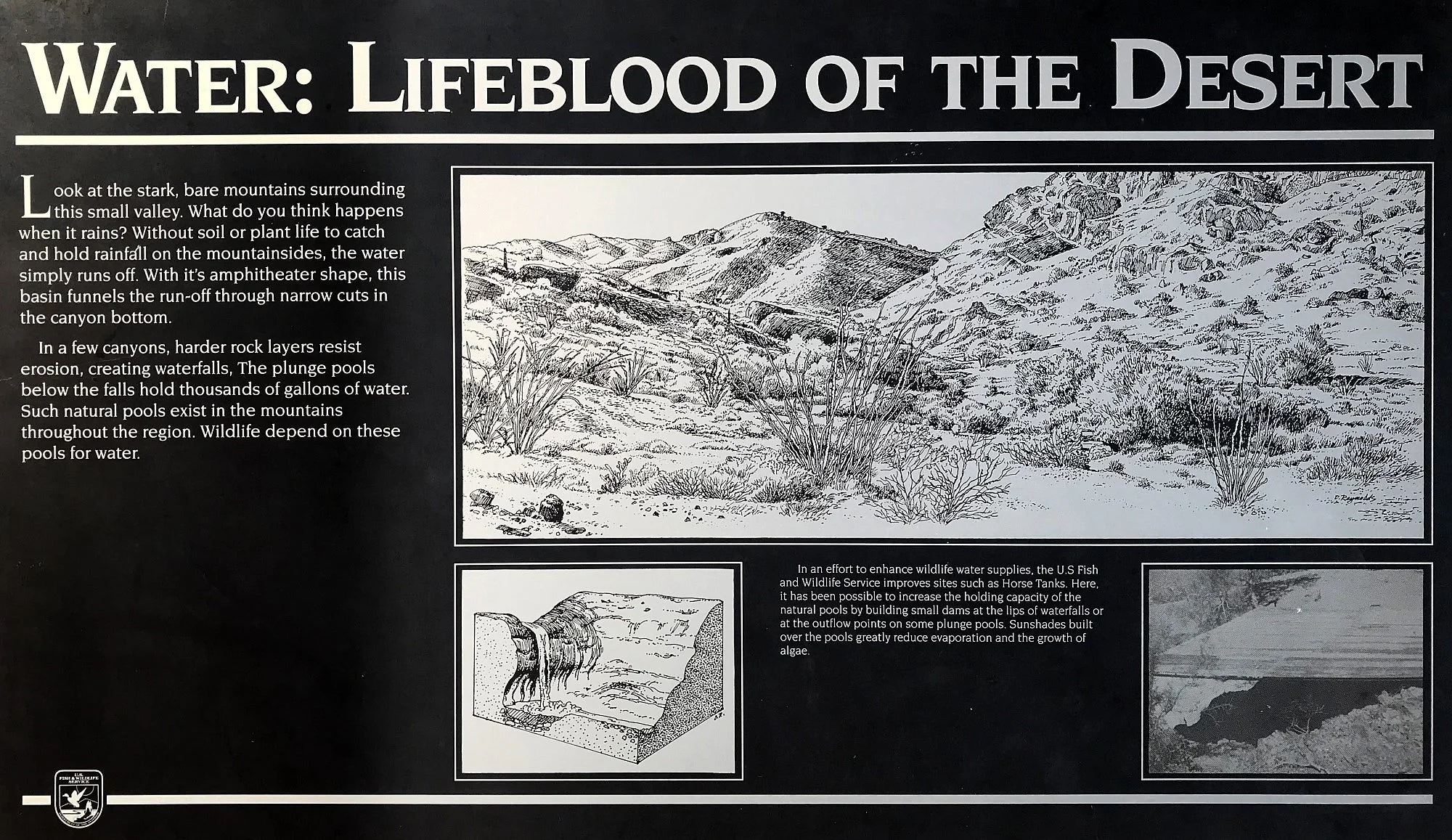

Tanks: desert watering holes

Wintering RVs are sometimes scattered along the first miles of the few gravel roads that provide entry into the Refuge. Grateful for our Sportsmobile’s rough-road capabilities, we progressed further and bush-camped near Horse Tanks. This area has provided reliable water sources for a long time, as evidenced by the plentiful animal tracks, the rock art and many bedrock grinding holes (morteros) in caves and dry washes.

Interpretive signage explains how a natural tank is formed.

It never rains in California.

But girl, don't they warn ya?

It pours, man, it pours.

Kofa’s desert environment has benefited this year from the atmospheric rivers that pounded the Pacific coast. Pools were full, Loggerhead Shrikes were snacking on abundant insects and barrel cacti were as plump as bloated ticks.

Glimpses into the Past

There were two old cave dwellings fairly close to our camp. One (top image), is quite expansive and looks quite cosy.

The other cave (middle row) was across the wash from us, halfway up a hillside and is not much more than an extended overhang. However, it contained petroglyphs and grinding holes. There are more grinding holes down in the valley along the river bed (bottom row).

Try to imagine the daily activities of people who had sheltered centuries ago in this Kofa cave. Did it feel like home? Was life good?

It pours, man, it pours

Next afternoon, California’s stormfront caught up with us.

Rain and wind gusts increased, lightning played against the red hillsides and thunder echoed down the canyon. The tanks were at capacity and overflowing.

A stream of run-off bustled by our Sportsmobile. Winter storm in the Sonoran Desert – doesn’t get better than that!

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona

Making sense of the landscape: an overview

The Sonoran Desert

Named after the state of Sonora, Mexico, the desert ranges between sea level and 3,000 ft. It is the hottest desert in the United States, experiencing large fluctuations in daily temperature combined with rainy seasons in winter and late summer. These climatic forces have sculptured the dramatic landscape and provide soil, slope, and exposure for plant life.

Basin and Range

Monument landforms are dominated by steep, blocky, northerly trending mountain ranges and intervening flat desert basins – typical of the extensive Basin and Range physiographic province of western and southwestern United States and northern Mexico.

Mountain slopes are rugged and precipitous, with surface rock bare or covered with only a veneer of talus. There are few seeps and springs and no permanent streams. Periodic, sometimes torrential rainfall, has carved the mountains, molded alluvial fans, and built the gently sloping outwash plains (called bajadas) that spread out from the canyons into the valleys.

Continental drift

Tectonic forces stretched the Earth’s crust, with vertical displacement along breaks (called normal faults) in the rock strata. An uplifted block bounded by normal faults is termed a horst (e.g.: Mt. Ajo). A downdropped block, between horsts, is termed a graben and these comprise the intervening valleys.

Valleys between ranges are troughs partly filled with debris eroded from the mountains. The centers of the valleys are wide, nearly level plains comprised of clay and silt which may be hundreds of feet deep in places.

Volcanism

Two episodes of crustal extension are recorded; an early period lasted from about 36 million years (m.y.) ago until about 17 m.y. ago. Extensive volcanism took place during this extension, and most of the volcanic rocks in the Monument were erupted at this time. A later period of extension began about 10 m.y. ago and ended about 5 m.y. ago.

Most of the rocks in the Mt. Ajo area have been deposited by igneous volcanic processes and include granodiorite, rhyolite, obsidian, andesite, dacite, latite and basalt.

Water drainage

A major proportion of rainfall runoff passes west and northward by means of a system of arroyos and sandy washes into the usually dry bed of the Gila River. About one-fifth of the monument area drains south into the Sonoyta River of Mexico, thence toward the Gulf of California.

These well-defined drainage systems indicate that a long time has elapsed since the occurrence of earth movements that gave rise to the present surface features.

Adapted from:

Interpretive Geologic Map of Mt. Ajo Quadrangle, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona. J.L. Brown, U.S. Geological Survey. 1992.

National Park Service, Natural History Handbook, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Last modified 11/4/2006.

Biodiversity

An impressive array of 28 species of cacti exist in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Biodiversity is the variety of life on Earth and is essential for our survival. It provides us with clean air and fresh water, natural control of pests and diseases, healthy soils, food, fuel, medicines, and mental health. Biodiversity engenders resilience against adverse events.

Top row: Left - Great Basin Collared Lizard; Right - Cholla skeleton & California poppies.

Second row: Left - Mohave desert star; Right - Bee at buckhorn cholla.

Third row: Left - Curve-billed Thrasher; Right - Beware: Prickly Pear.

Fourth row: Left - Alamo wash; Right - buckhorn cholla (flowers can be a blend of yellow, orange & red).

Fifth row: Left - Ajo Range; Right - Englemann prickly pear.

Bottom row: Left - Trail into Alamo wash; Right - Mammillaria spp.

Extinctions

There have been three waves of human-caused biodiversity loss.

The earliest was the Quaternary extinction of megafauna by hunting.

The second started with settled agriculture, when humans began reshaping ecosystems to better meet their needs for food and materials.

Our industrial revolution ushered in the third wave, when ecosystem domination became prevalent. We are the evolutionary force that will decide the fate of every species, as well as the habitats in which those species live.

From: Our Evolutionary Impact. B. Shapiro. The Climate Book, Ed. G. Thunberg.

Left: Passing over Interstate 5 in California’s Central Valley. Note the monoculture of almond trees & the fossil-burning transportation.

Right: Looking down on Twin Peaks campground (Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument) with its multitude of RVs (our’s included).

The Anthropocene

In 2008, the Stratigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of London, concluded that Earth had transitioned from the Holocene to the Anthropocene Epoch and charged a subgroup to define when it started. The Working Group, in 2015, recognized the “Great Acceleration” of the mid-20th century as the beginning of the Anthropocene. Further research indicates that plutonium and other radiogenic fallout from atomic bombs post-1945 are a consistent signature in the the world’s geological record.

Now, our globalized existence constitutes the largest driver of change on Earth and we are sliding towards a mass extinction of species, the sixth in our world’s last half a billion years. To achieve a sustainable future, an urgent, over-riding goal is to restore high-biodiversity ecosytems that provide resilience against climate change.

Adapted from: (1) Terrestial Biodiversity. A. De Palma, A. Purvis. The Climate Book, Ed. G. Thunberg. (2) This is Epoch. M.E. Hannibal. Stanford, May, 2023

Top row: Left - Ocitillo flowering; Right - Alamo sunset.

Second row: Left - Palo verde; Right - Native grass, species unknown.

Third row: Left - Thistle, species unknown; Right - Seep monkey flower.

Fourth row: Left - Gordon’s bladder pod; Right - Brassica spp.

Fifth row: Left - Mallow spp; Right - Desert lupine.

Sixth row: Left - Saguaro flower buds; Right - Chain-fruit cholla.

Seventh row: Left - Cactus Wren; Right - Gila Woodpecker.

Bottom row: Left - Teddybear cholla; Right - Buckhorn cholla.

Ranger Evening Programs

We attended two informative presentations by Parks Rangers that touched on biodiversity and conservation in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The area’s biodiversity is enriched by several relict species - populations that were more widespread or more diverse in the past.

Organ Pipe Cactus

Organ pipe cacti originated in the tropics but migrated northwards when the world thawed after the Ice Age ended, reaching the higher-latitude limits of their range in the Monument’s warmer, southwest-facing slopes. The flowers open at night in June and are pollenated by nectar-feeding lesser long-nosed bats that migrate up from Mexico.

Relict species

Other relict species include juniper and pinion pine atop Mount Ajo, live scrub oak in moist Alamo Wash, desert pupfish, reptiles such as the Sonoyta mud turtle and venomous Gila monster, and the desert pronghorn – which evolved to outrun extinct cheetah-like relatives of the mountain lion and is now much faster than it needs to be.

Will these relict species survive as the climate changes and adverse tipping points are reached?

Sonoyta mud turtle: image by T. Pierson, iNaturalist

Creosote bush

Black-tailed jackrabbits are the only known mammal species to eat the bitter-tasting leaves of the creosote bush (Larrea tridentata). Turns out that this widely distributed plant was probably better utilized in the past – by prehistoric camels.

Left: Creosote flowers and seeds. Right: Actually, this rabbit is a desert cottontail. Cute.

Endangered hominid

It is likely that this relic will go extinct.

Border Wall

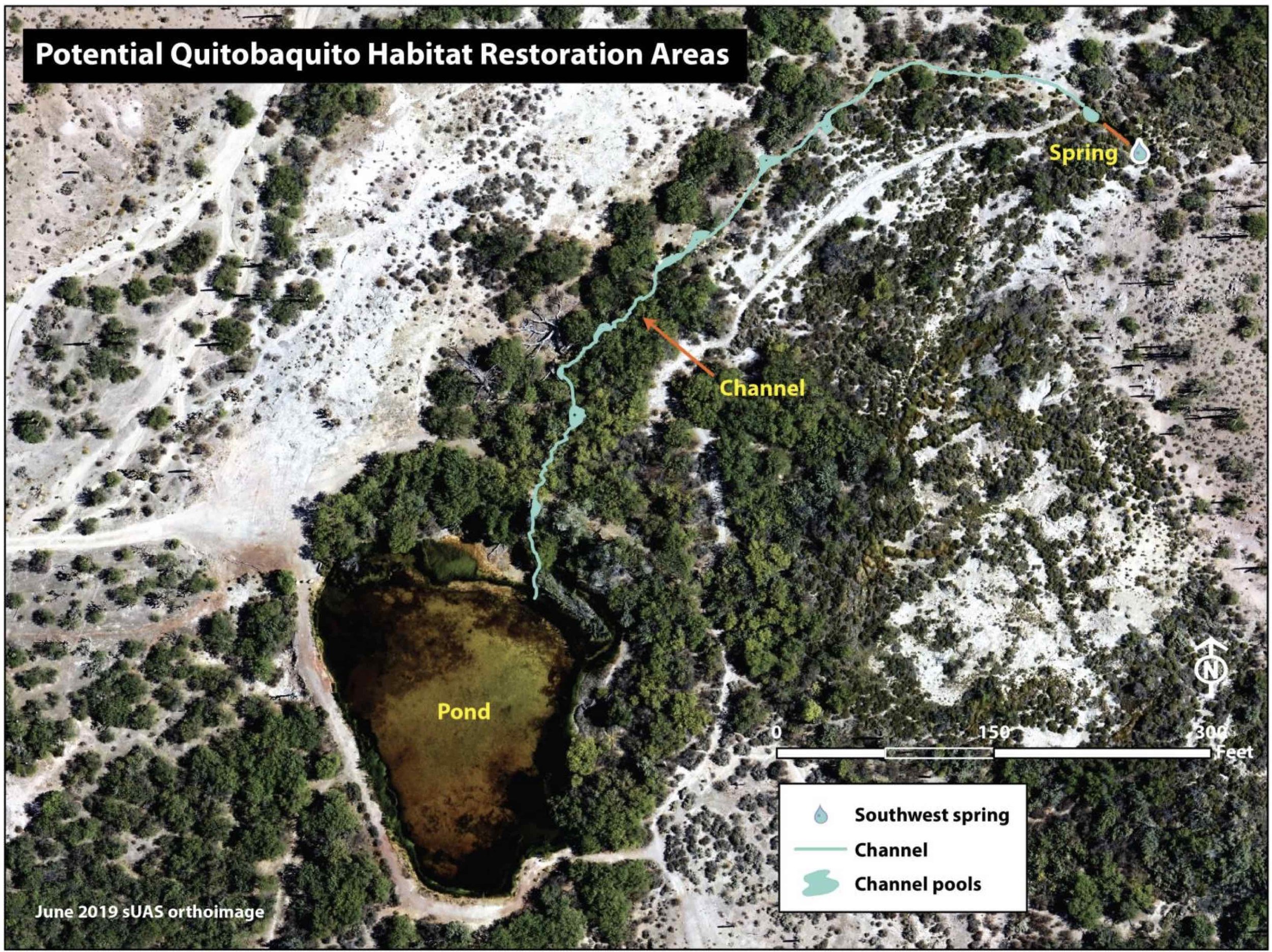

In 2022, the National Park Service intervened at Quitobaquito Springs to stabilize water levels.

Scientists noted diminished spring flow after the groundwater pumping, dynamiting and vegetation disruption conducted during border wall construction. This, along with leakage from the Springs’ man-made pond were threatening the survival of the endangered Sonoyta mud turtle and Quitobaquito pupfish.

Results of the restoration project are being monitored.

Unexpected

I was photographing a nesting Phainopepla and had positioned my camera’s tripod across a hiking trail.

After about 25 minutes, I gradually became aware of a persistent scratching noise behind me. Glancing backwards, I was amazed to find a desert tortoise plodding along by my right foot. It paused when I stiffened with surprise but soon resumed its journey and marched between the tripod’s legs. My 600mm lens cannot focus as close as my toes, so I simply enjoyed the moment with this ancient desert wanderer. However, before it disappeared around the trail’s bend, I snapped a memento of the magic encounter.

The Monument’s geology is typical Sonoran Desert Tortoise habitat. Landforms include deeply incised washes with numerous caliche caves, as well as steep hillsides with boulder piles and rock ledges. Shelter sites and forage are adequate.

An Arizona Game and Fish Dept. report in 2016 by C. A. Rubke, H. A. Hoffman, and D. J. Leavitt was the first attempt to estimate occupancy for Sonoran Desert Tortoises at the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. They found that 31% of all predicted habitat should be occupied by the tortoises.

Saguaros

Each saguaro has a unique shape. Collectively, they are mythological.

Saguaros retain a lot of moisture and their side branches can weigh hundreds of pounds. These arms usually curve upward gradually because that shape provides the optimal biomechanics to support such weight.

Sometimes, saguaro arms bend downwards. It is thought this happens when the plant’s fibrous skeleton is weakened by a hard frost, causing the arm to rotate and droop.

Natural cycles of Fauna & Flora

We visited Organ Pipe Cactus Monument twice, once in early March and then later, during the fourth week of April.

It was instructive to note the Spring changes over time and witness the lovely flowering progression of Sonoran Desert vegetation.

Top row: Left - Brittlebush; Right - Desert beauty.

Second row: Left - Mallow spp; Right - Aster spp.

Third row: Left - Fairy duster; Right - Geranium family.

Fourth row: Left - Aster spp; Right - Desert rose mallow.

Fifth row: Left - Baby bonnets; Right - Rock hibiscus.

Sixth row: Left - California poppy; Right - Blue dicks.

Seventh row: Left - Sunset; Right - Twilight.

Eighth row: Left - Saguaro trunk; Right - Prickly pear spp. growth bud.

Ninth row: Left - Saguaro; Right - Curve-billed Thrasher taking insect to nest.

Tenth row: Left - Chain-fruit cholla; Right - Jojoba fruit.

Tenth row: Left - Teddybear cholla; Right - Pricky pear spp.

Eleventh row: Left - Prickly pear spp; Right - Golden hedgehog cactus.

Twelth row: Left - Prickly pear spp detail; Right - Bee at buckhorn cholla.

Bottom row: Left - Ajo range sunset; Right - Waxing moon.