Chasing the Southwest Monsoon: September & October, 2023

Section #1: The Early People

After the rain.

Sunset in Glen Canyon National Recreational Area, Utah.

Black-chinned Hummingbird (female/juvenile).

“We have lived upon this land since days beyond history’s record, far past any living memory, deep into the time of legend. The story of my people and the story of this place are one single story. We are always joined together.”

From tribal manifesto of the Red Willow People, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico

Mount Irish petroglyph, Nevada.

Gaillardia pulchella (Blanket flower)

Mule deer.

Acorn Woodpecker, male.

Southwest again?

We considered heading north to Montana, but after our Southwest tour in Spring and the Klamath sojourn in June, we opted to remain local and relish California’s idyllic Mediterreanean summer. Northern US can turn a mite chilly in Fall (we are, after all, children of the tropics), so we revised plans and departed late-August to revisit the warmer Southwest. Chihuahuan Desert cacti had bloomed spectacularly after winter’s copious storms and we were curious to witness the botanical response to summer’s monsoons. Additionally, we wished to experience Southwest’s high country and learn something of the region’s pre-Columbian human history.

Route

Follow the red dots (our campsites) in a clockwise direction. We left San Francisco Bay, traversed the Sierra range via Yosemite and went eastward into Nevada, Utah and Colorado. Then turned southward to visit New Mexico and Texas. Big Bend National Park was our most southerly location. Re-entering New Mexico, we explored the Gila Wilderness before transitioning to SE Arizona. Next, we journeyed NE to Arizona’s high country. From there, we headed westward, crossing the Colorado River into Nevada and pushing through California’s Mojave desert to reach the Central Valley. Home the following day, the 59th of the trip.

Rio Grande demarcating the US/Mexican border, Big Bend State Park, Texas.

What did we learn?

As usual, our primary objectives were botanical, avian and exploring the US.

In retrospect, our brief inquiry into early North American cultures was wonderful. It added significant nuance to our perceptions of current situations and provided longitudinal knowledge that may have relevance going forward. With that in mind, this account of our travels will span the continuum from the past to the future.

Fremont cottonwood leaves in Walker Creek, Arizona.

Benton Hot Springs, California

Our first stop of the trip – a delightful soak!

Each campsite has its own private hot tub. Definitely living in the present!

Left: Lizard Tail (Anemopsis california) graces the fringes of springs and wetlands. Right: Our van seemed tiny compared to the neighbor’s house-sized trailer.

Mount Irish Archeological District

Situated on the eastern flank of Nevada’s Mount Irish Range, the 640-acre property contains numerous prehistoric rock art sites set within a stunning volcanic landscape. Prior to Euro-American colonization, Eastern Nevada was settled by hunter-gatherer cultures who survived on the wild resources of this arid region for several thousand years. These peoples lived in small, mobile family groups.

The monsoon season was in full swing; clouds hung low overhead, the vegetation was vibrant and the sandy washes held pools of water.

All images: Mount Irish Archeological District.

Hunter-gatherers

The Mt. Irish area was used for short-term stays to hunt animals, gather plants, and make rock art. These repeated visits stretch back as far as 4,000 years ago but became more intensive and frequent during the period 2,000-500 years ago. Many rock art sites contain the remains of campsites such as rock shelters and middens. Stone tools and grinding stones show that animals and plants were often processed in the vicinity of rock art.

There are two Rock Art styles described.

Rock Art style #1: Pahranagat

The Pahranagat Style is found mostly in the Pahranagat Valley within Nevada’s Lincoln County. People are portrayed in two very different ways. One form has oval or rectangular solid-pecked bodies, large eyes, a short line protruding from the head, and hands that have long fingers.

Human figures

The other Pahrangat depiction of human form is a rectangular body that has geometric designs or straight lines inside and stick-figure arms and legs. Sometimes these are portrayed holding objects that resemble atlatls (dart throwers) suggesting this style was made before the bow and arrow was widely adopted in the region some 1,500 years ago.

Rock Art style #2: Basin and Range

Basin and Range Style rock art comprises finely made abstract designs, portrayals of people as stick-figures, and a wide range of animal species, most commonly bighorn sheep.

Interactions between cultures

Some sites include rock art of the Ancestral Pueblo style. These images, along with Pueblo pottery fragments, indicate that eastern Nevada hunter-gatherers had cultural contact with ancient Pueblo groups during the period 2,000 to 850 years ago.

Mount Irish

The area and rock art are important to today’s Native Americans who live in the region. The district is managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and is accessed by a dirt road.

It was a pleasant surprise to find that a primitive campsite was in the process of being built in the general vicinity of the petroglyph sites. We had the new facilities to ourselves during our 5-day stay. Logan City, a silver mine ghost town is nearby and well worth a visit - a hike of a few miles from camp.

Loved the place!

Our overriding thought was profound gratitude for the privilege of viewing the ancient art, magnificently displayed in the place it was created. The rock art sites evoke feelings of reverence and awe. One can appreciate a common bond with nomadic folk who lived thousands of years ago.

The entire place had drama. Monsoon thunderclouds crashed overhead, opaque mist draped the mountain peaks, coyotes serenaded the dawn. During the day, hummingbirds buzzed among the dense sagebrush.

Arrival of humans in the Americas: the Southwest story

My minuscule understanding of this topic is gleaned from several recent books and peer-reviewed articles.

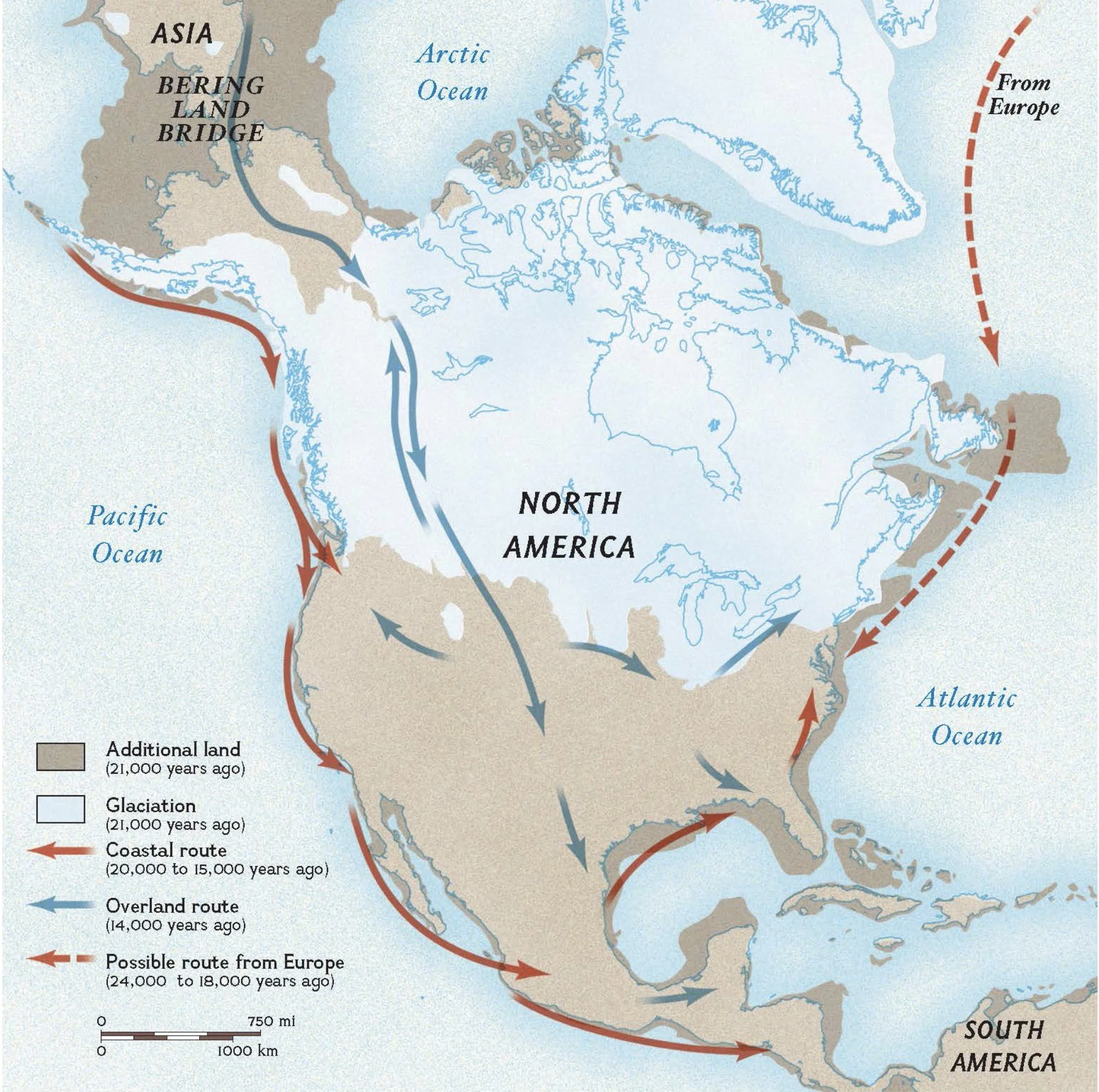

Humans arrived in the Americas via two major routes. One route involved passage over land. During the last ice age sea levels dropped because so much water was held as ice. A land-bridge, 600 miles wide, emerged between Asia and America at the Bering Strait. This bridge supported grasses and shrubs, animals and humans. As North American glaciers began to thaw, groups of people migrated southwards about 16,000 to 14,000 years ago along an ice-free corridor that opened along the eastern margin of the Rocky Mountains.

An older, perhaps busier route was maritime travel along the Pacific Rim – the “Kelp Highway”. Northeastern Asian people used skin boats to move along the coast, harvesting the rich marine and estuarine resources to reach as far south as Chile by 16,500 years BCE. Some have suggested that coastal migration also occurred from Europe.

Proposed routes of human migration to the Americas

Homo sapiens in North America

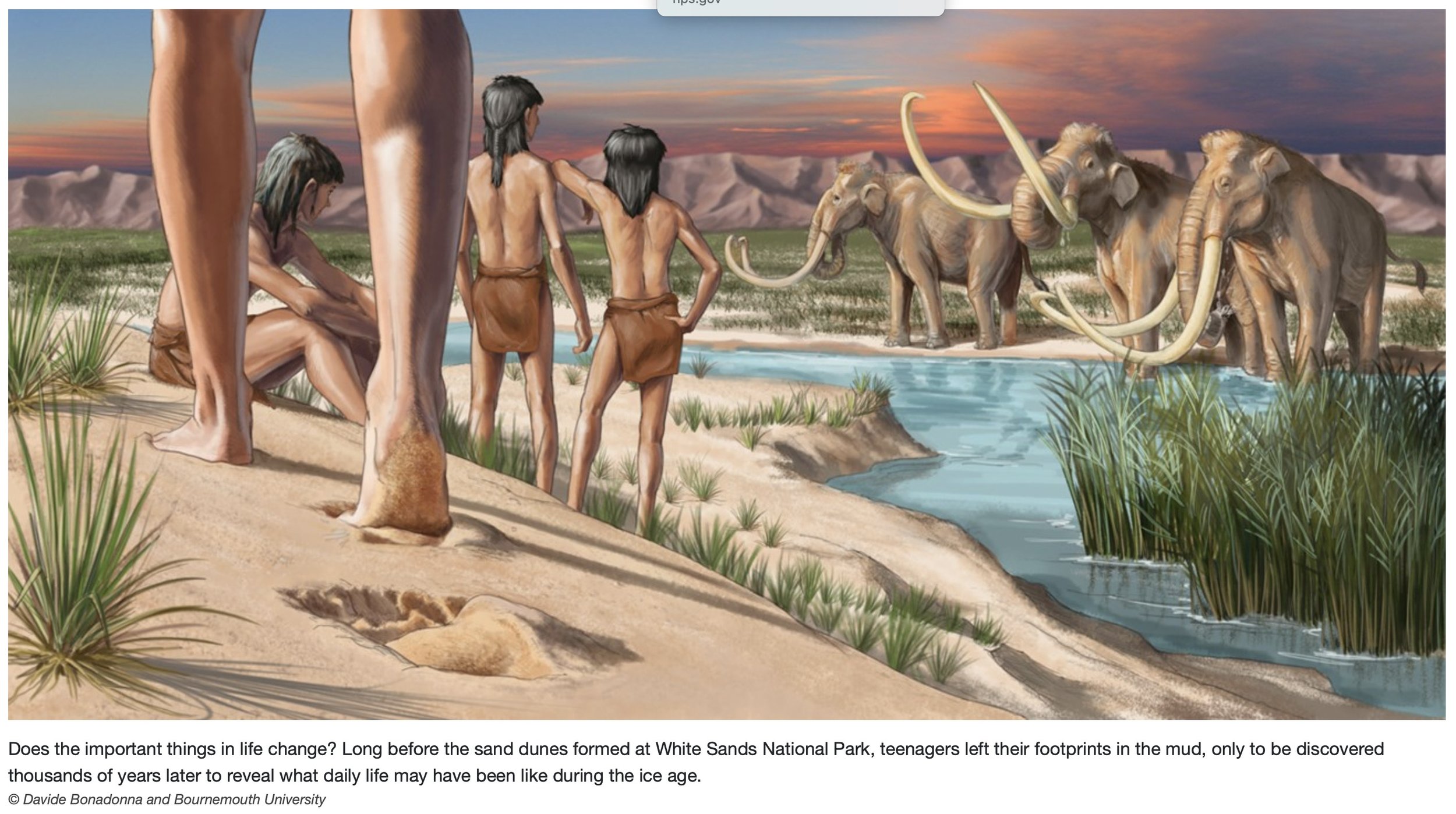

The earliest evidence of humans in North America dates to 23,000 BCE (Before Common Era) and are footprints found in New Mexico’s White Sands National Park. Recent analysis of the tracks (J. S. Pigati et al., Science 382, 73; 2023) confirms that humans were present in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum and implies that early inhabitants and megafauna coexisted for several millennia before the terminal Pleistocene megafauna extinction event.

Graphic: National Parks website.

End-Pleistocene Extinction

In North America, 32 genera of large mammals - including mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths, and giant beavers, were lost over a 2,000 year period, centered on 11,000 BCE. Small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians were generally spared.

Two causes are proposed: (1) the extinctions were the result of over-predation by human hunters; and (2) they were the result of abrupt climatic and vegetation changes during the last glacial–interglacial transition.

The first theory predominates these days, as elegantly described by Beth Shapiro and Elizabeth Kolbert (chapters 1.3 and 1.4, The Climate Book). In every continent except Africa, megafauna extinctions coincided with the first appearance of humans in the fossil record.

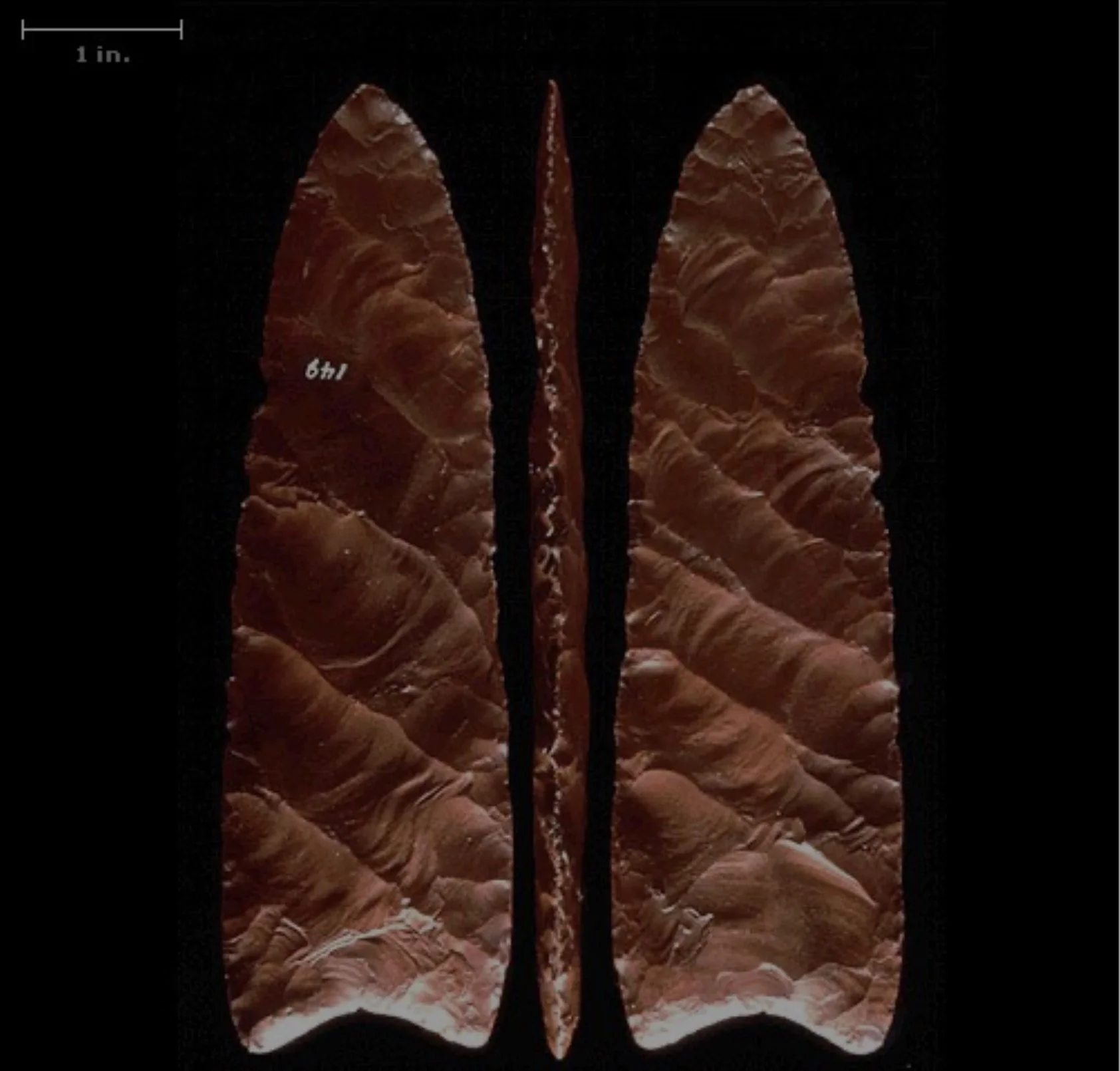

The Southwest features prominently in the North American story. Clovis archaeological sites (first described in 1929 at Clovis, New Mexico) are an appropriate example. The Clovis culture was widely distributed throughout North America and date to about 10,000 and 12,000 years ago. It preceded the Folsom culture (discovered in 1908 at Folsom, New Mexico). Both groups were hunter-gatherers. Clovis people hunted Pleistocene megafauna and designed a spear point appropriate to the task. Folsom hunters used a different spear point design that was more suited for hunting prehistoric bison, probably because megafauna were disappearing and bison were thriving on the new grasslands that proliferated as the continent warmed. It is also thought that human manipulation of the environment (e.g.: fire) was a factor.

Abrupt climatic change also occurred at the time of the megafaunal extinctions in some continents but, importantly, not in Australia or New Zealand. Certainly, it is feasible that climate perturbations affected food type and availability. It may be that both climatic change and human activities played roles but of varying importance in different situations.

Clovis spear point

The typical Clovis point is leaf-shaped, with parallel or slightly convex sides and a concave base. The edges of the basal portions are ground somewhat, probably to prevent the edge from severing the hafting cord. Clovis points range in length from 1.5 to 5 inches (4 to 13 centimetres) and are heavy and fluted, though the fluting rarely exceeds half the length.

To make the point, Clovis knappers used a billet, a hammer of ivory or antler, to flake off pieces of the point through a process known as brittle fracture.

(https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/ancient-clovis-cache/)

Rising moon above Mount Irish, Nevada