Summer in the Klamath Mountains: June – July 2023

Ocean fog forming after sundown along the California / Oregon coast.

Bigelow’s sneezeweed with unidentified red insect.

Aster spp.

Rufous Hummingbird, immature male/female.

“We are all relatives, not resources.” Yurok tribal member

The worldview of the indigenous Klamath people holds belief that living resources and culture are singular, with nature completely intertwined with humanity. Language, customs, ceremony, cultural development and food resources evolved synchronously, not independently.

From: The Klamath Mountains, a Natural History. Eds: Kauffmann & Garwood.

Anna’s Hummingbird, female

Ridge crest at Sanger Peak, Klamath National Forest

Stream orchid

Mallow with pollinator

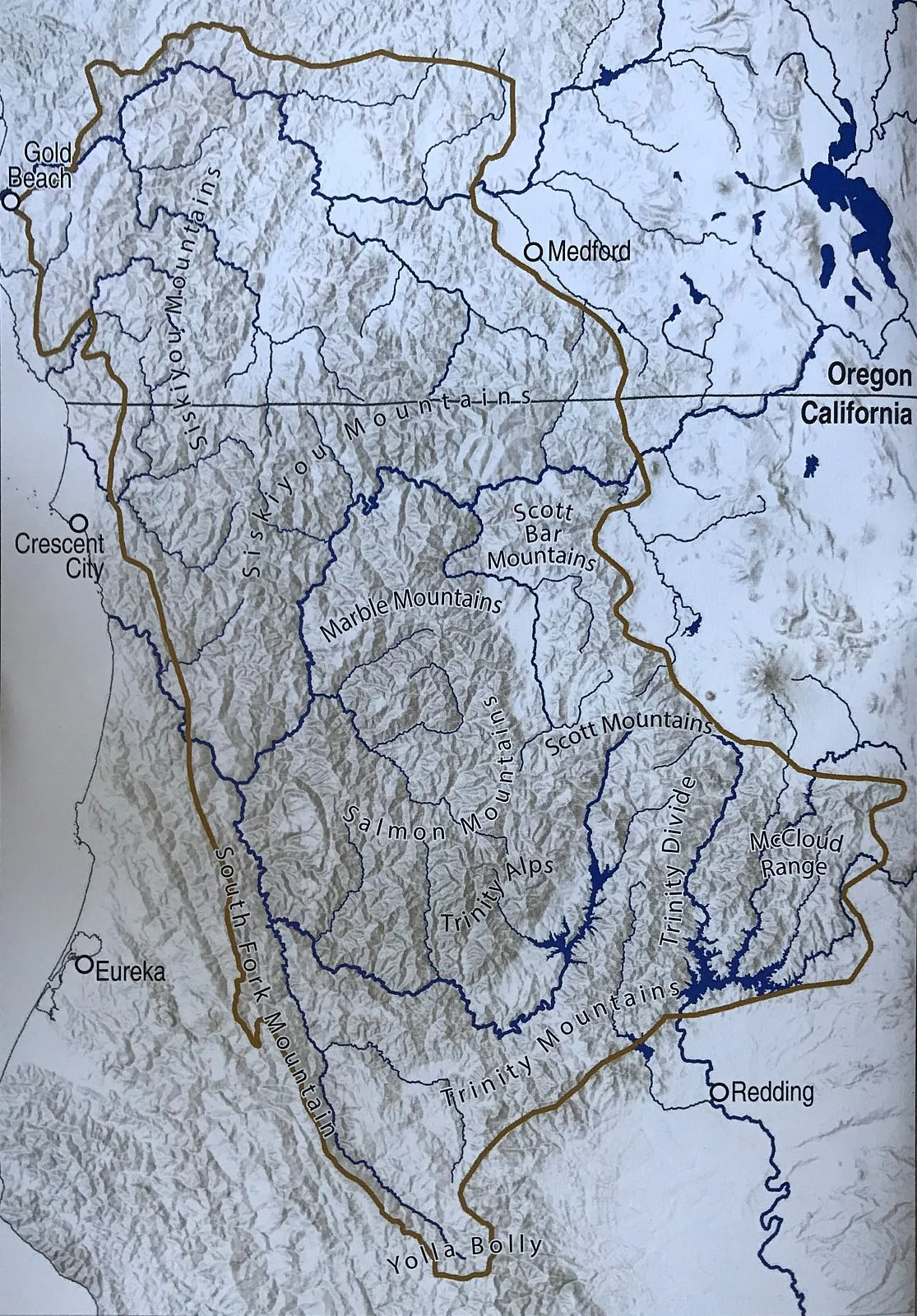

Klamath Mountains Bioregion

The Klamath Mountains Geomorphic Province of NW California encompasses watersheds of the Rogue, Pistol, Chetco, Smith, Klamath, Trinity and Sacramento Rivers.

The Province is an important and impressive biodiversity refuge because it is located at a complex crossroads of a variety of biotic communities.

The limits of the Klamath Mountains Geomorphic Province are indicated by the thick brown line.

Figure from: The Klamath Mountains, a Natural History. Eds: Kauffmann & Garwood.

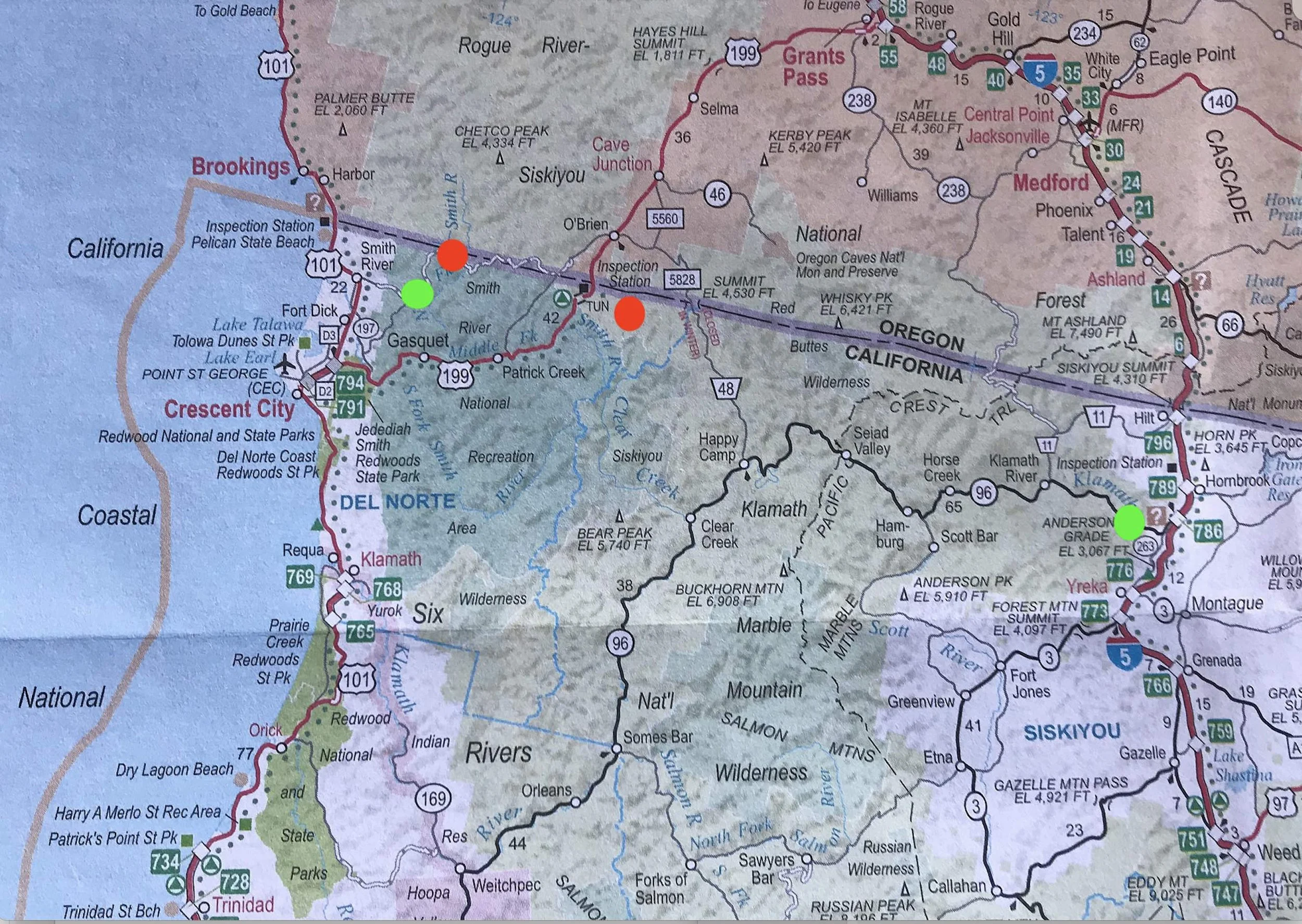

Route

We entered the region via Interstate 5, turning west onto Highway 96 to reach Tree of Heaven campground alongside the Klamath River. At Happy Camp we drove north on Highway 48 into Oregon and then, at O’Brien, headed west again into California, following the energetic flow of the Smith River’s middle Fork.

We overnighted at two locations (green dots) and set up camp at two sites (red dots), staying for a week at each.

The location of these campsites were:

A National Forest campground (874 ft elevation) on the North fork of the Smith River in the Six Rivers National Forest.

A meadow (5350 ft elevation) near Sanger Peak in the Klamath National Forest.

What were we doing?

Our primary objectives were botanical and avian, hoping to discover delightful variety in species, color, form, and survival adaptations in our surrounding natural environment. Of course, one should not discount the sense of adventure and freedom inherent in wilderness camping and a 4x4 road trip. We had a good time.

Acmispon spp

Unidentified beetle snacking on morning glory

Natural History

“The practice of intentional, focused attentiveness and receptivity to the more-than-human world, guided by honesty and accuracy”

Bookworms

Traveling with a well-stocked library is one advantage of campervan life. Michael Kauffmann and Justin Garwood’s recently published book on the Klamath Mountains was invaluable to us. It is a comprehensive account of the region’s biodiversity and discusses the effects of long-term human habitation on the environment.

Accreted Terranes

In the Cambrian Period, 537 million years ago, the current western portion of North America was open ocean. About 400 million years ago, driven by continental drift, pieces of island arc volcanoes started colliding and fusing with the edge of the continent. These plastered-on chunks of thickened lithosphere are called accreted terranes. The concept of accreted terranes was first developed around 1960. The Klamath region is considered an example of accretionary mountain building and continental growth.

At the Smith River’s north fork, we were on the Western Klamath terrane, which was the last terrane in the Klamath Province to fuse onto continental land - about 157 million years ago.

An ophiolite sequence is a characteristic suite of rock types that represent a cross section of the crustal and upper mantle rocks which comprise an oceanic plate. Ophiolite sequences are composed primarily of ultramafic rock with a covering of seafloor crust and oceanic sediment on the top. We were surrounded by Josephine ophiolite, which has harzburgite, an ultramafic rock with a distinctive orange color.

From: Geologic History: Mark Bailey in The Klamath Mountains, a Natural History.

Early morning light penetrates coastal fog remnants to reveal burnt Jeffrey pines on an orange hillside of Josephine ophiolite.

Serpentinite-associated flora

When the young Earth was molten, heavier minerals sank inwards and the lighter floated to the surface. If a rock contains abundant magnesium and iron, it tends to be dark and heavy and is referred to as mafic. Rock even richer in these elements is called ultramafic.

Serpentinite rock has ultramafic origins and can be formed wherever ultramafic rock is infiltrated by water poor in carbon dioxide (e.g. at subduction zones).

Serpentinite rock is rich in magnesium, iron and other minerals that constrain the metabolism of many plants. However, some species have adapted to these soils. The Josephine opiolite has 70 endemic plant species – more endemics than any other serpentine outcrop in North America.

Adapted from: The Klamath Mountains, a Natural History. Eds: M. Kauffmann, J. Garwood. 2022, Backcountry Press, Kneeland, CA.

The whiteleaf manzanita and hoary manzanita are both serpentine-associated and were growing around our camp. Manzanitas have evolved to tolerate summer drought, cool wet winters, and frequent fire. Trevlyn spent many hours of many days identifying the various species by deep consultation with formidable botanical tomes. In the end, some uncertainty remained because the salient features seemed so variable.

Darlingtonia californica

Carnivorous plants grow in places where nutrients are deficient. In the Klamath Mountains this often means peatlands and/or serpentine soil.

The Cobra plant lures insects into its long, hollow stem where they cannot escape. The plant harbors bacteria and protozoa that digest the insects and share the nutrients with their host.

North fork of the Smith River

Access to the area involves a rough, dusty drive for 25 miles. Perhaps this explains why we were the sole occupants in the 6-site National Forest campground for most of our stay.

The river is gorgeous and warm enough for swimming. An Osprey hunted the calmer pools between rapids.

The river was our source of drinking water.

The Foothill yellow-legged frog is largely restricted to streams and rivers below 4,000 ft.

Birding

Bird species seen daily around our Sportsmobile included Western Tanager, Spotted Towhee, Rufous and Anna’s Hummingbirds, Black Phoebe, Northern Flicker, Common Raven, Downy Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, American Robin, Black-headed Grosbeak, Hermit Thrush, Warbling Vireo, Western Wood-Peewee, Spotted Sandpiper, Violet-green Swallow, and Steller’s Jay.

Opposite: Spotted Towhee with lunch for fledgling.

Below: left to right: Stellar’s Jay, fledgling Spotted Towhee, Western Tanager.

Hummingbirds

OK, too many hummingbird pictures. Apologies for the indulgence! All are Rufous Hummingbird, female/immature male.

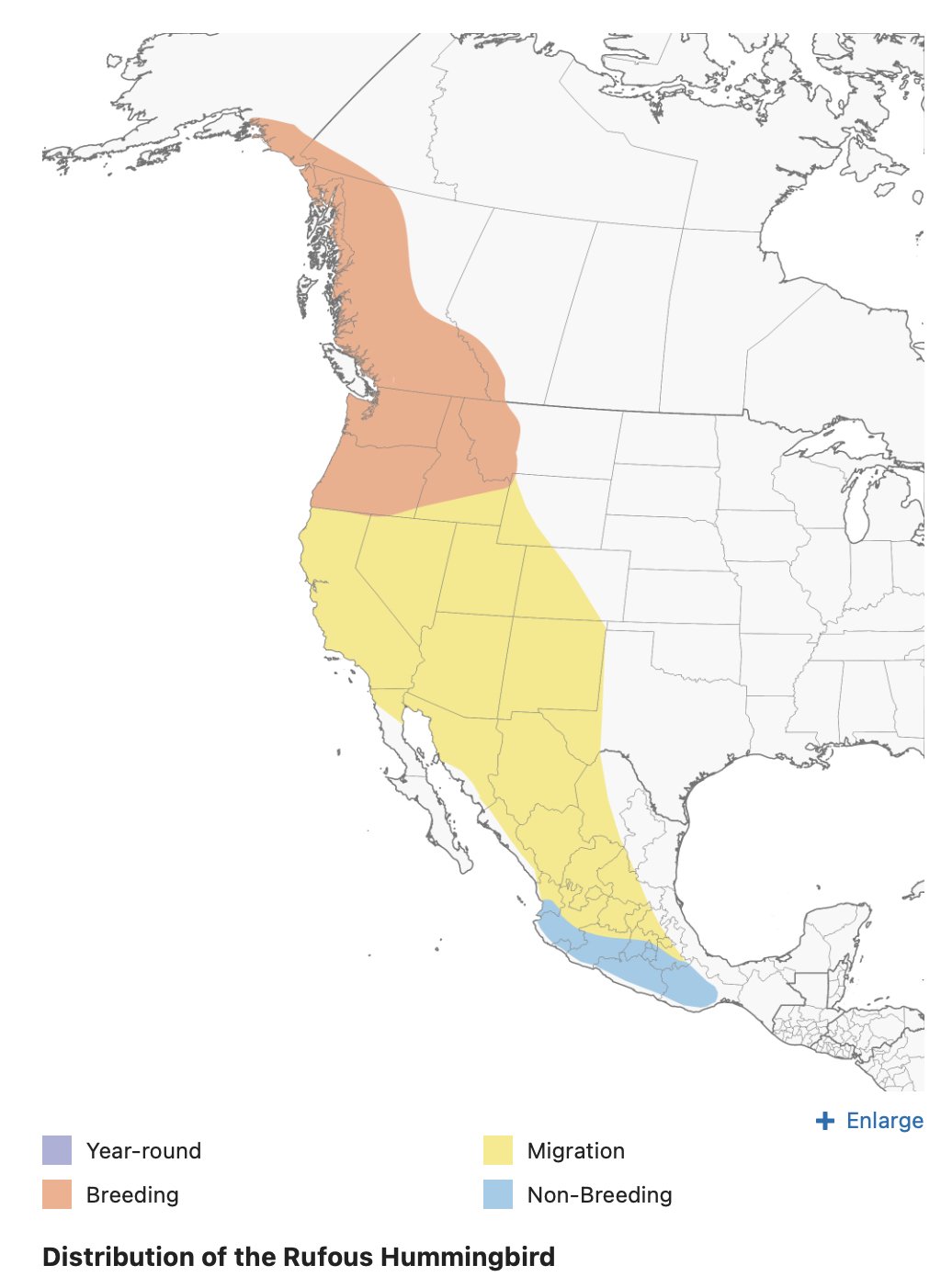

Rufous Hummingbird migration

The Rufous Hummingbird is North America's “extremist” hummingbird. Venturing far from the equatorial tropics in which its ancestors evolved, it reaches the northernmost latitude of any hummingbird (61° N). After making the longest (measured in body lengths) known avian migration, individuals from Alaskan populations face a short breeding season but the longest day-length seen by any hummingbird.

It is a complete migrant, vacating breeding grounds for wintering grounds primarily in Mexico. The species generally follows lowland coastal route north in spring, highland route (alpine meadows) south in summer/fall - tracking areas with most abundant flowers.

Timing of migration generally related to floral phenology--when flowers open. Males tend to precede females in northbound migration, arriving on breeding grounds about a week before females.

For the journey south, most males in British Columbia have left breeding grounds by mid June to early July. Females begin to leave about a week after their young fledge; most have left by late June or early July. Fledglings leave soon after adult females depart.

From: Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Botanical treasures

Nestled within a tiny floodplain, the plant display in close proximity to camp was in full bloom and was a source of delight.

Nighthawk camp

After a day of slow-paced botanizing, we camped overnight on a ridge. To the east, we could see Pine Flat and the deep gorge cut by the Smith River’s north fork. Looking west, the Pacific ocean shimmered in the late afternoon light. Towards sunset, a thick marine layer of fog materialized.

Common Nighthawk

Above us was a waxing moon and Common Nighthawks hawking insects at dusk. It was impossible to miss their loud, nasal peent calls, spectacular booming courtship dives, and erratic, almost bat like flight.

The Common Nighthawk has a large, flattened head with large eyes; small bill and enormous mouth - well suited for catching flying insects in low light. It nests most often on open ground, gravel beaches, rocky outcrops, burned-over woodlands, and flat gravel roofs, especially in cities. The bird makes no nest per se but usually lays its eggs directly on the ground; the cryptic plumage of this species makes nesting birds difficult to see. Both the female and male, which are similar in size and appearance, feed regurgitated insects to their chicks.

Recent data suggest a substantial decline in numbers of this species, perhaps owing to increased predation, indiscriminate use of pesticides leading to lowered insect numbers, or habitat loss. (From: Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

Next morning

When the sun crested the skyline at dawn, it touched a blanket of fog that had infiltrated the coastal valleys.

Meadow near Sanger Peak

Sanger Peak (5 862 ft) is in the Siskiyou Mountains. We went there to examine higher altitude vegetation and established camp in a meadow that contained a pond.

Northeast view from Sanger peak

Camp in morning light

The Pond

Thanks to this year’s good snow pack, the meadow was flourishing. Deer often came to graze in the evening. The pool was quite full and teeming with life.

Naturally, that included mosquitoes. We ended up adjusting our daily schedule to be inside the Sportsmobile an hour after sunset and stayed there until morning sunshine reached the meadow.

Pond fauna

Top row: Both images - insect larvae living underwater. Can anyone identify them?

Bottom row: Left - Tadpole with hindlegs; Right - Blue spp. feeding at the pond’s muddy perimeter.

Water Fairies

Fairy shrimp belong to the Order Anostraca and are among the most primitive of living crustaceans. Spiny-tailed fairy shrimp (Streptocephalus coloradensis) are generally restricted to the montane conifer belt between 4,000-7,200 ft. They are found in the Klamath Mountains in shallow, rocky, hard-pan, or clay-lined pools in depressions surrounded by conifers. The water is often stained brown with tannins derived from water-soluble decaying vegetation. Over 50 ponds in the Klamath Mountains Geomorphic Province contain spiny-tailed fairy shrimp.

Fairy shrimp require temporary ponds to complete their complex lifecycles. Like other animals that live in ephemeral waters, they benefit in having fewer predators compared to perennial waters. Their swimming paddles also serve as gills, salt regulation structures and appendages for food collection.

Reproduction

The female carries eggs in an ovisac where they form a thick, multilayered shell around each tiny embryo able to withstand extreme environmental conditions brought by desiccation and freezing. Once the eggs are ejected from the female they become cysts that persist for decades until key environmental signals induce hatching. In the Klamath Mountains, spiny-tail fairy shrimp cysts hatch into a new generation of larvae when snowmelt water refills temporary ponds each spring. Larvae then proceed through a series of molts to complete the annual lifecycle as adults.

Resilience

The major dispersal mechanism for fairy shrimp is the cyst. This rugged dust-like capsule sticks to an animal’s fur or a bird’s feathers. It also passes, unharmed, through the digestive tract of birds that eat female shrimps.

This female spiny-tailed fairy shrimp seemed to be burying her eggs in the soil.

Sanger Peak vegetation

Sanger Peak lies adjacent to Broken Rib Mountain botanical zone and the Siskiyou Wilderness. The area contains an unusually high concentration of conifer species because of the complex geology and the pattern of wildfire. We recognized Port Orford and incense cedar, lodgepole, Jeffrey and western white pine, Brewer spruce, and Douglas and Red fir.

1st row: Left - Jeffrey pines; Right - Brewer spruce.

2nd row: Left - Looking eastward into the Siskiyou Wilderness; Right - Broken rib mountain.

3rd row: Left - incense cedar; Right - Douglas fir.

Hummingbird flight

The following sequence lasted 0.6 seconds and shows the wing positions as the hummingbird sweeps them back and forth, generating lift the entire time.

Wingbeat frequency can be as high as 200 beats per second.