Travels in the Southwest: March & April, 2023 (#4)

Section #4

(Too much fun for just one blog post)

Theme #4: Chihuahuan Desert

Big Bend National Park: last light.

Greater Roadrunner: living up to its name.

Coyote, Rio Grande

Jules Leclerc, 1885

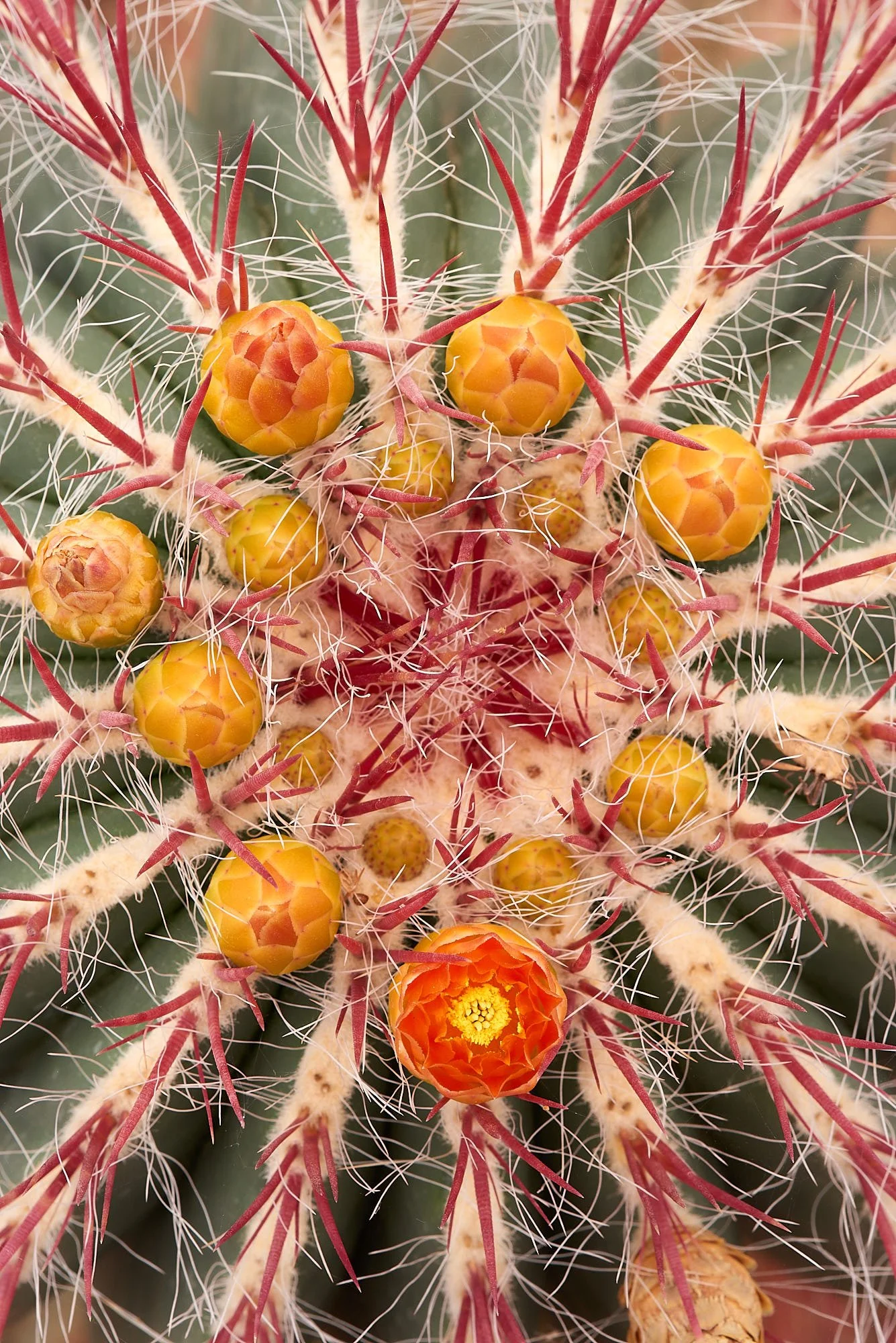

“Each plant in this land is a porcupine. It is nature armed to the teeth.”

Opuntia spp, Big Bend

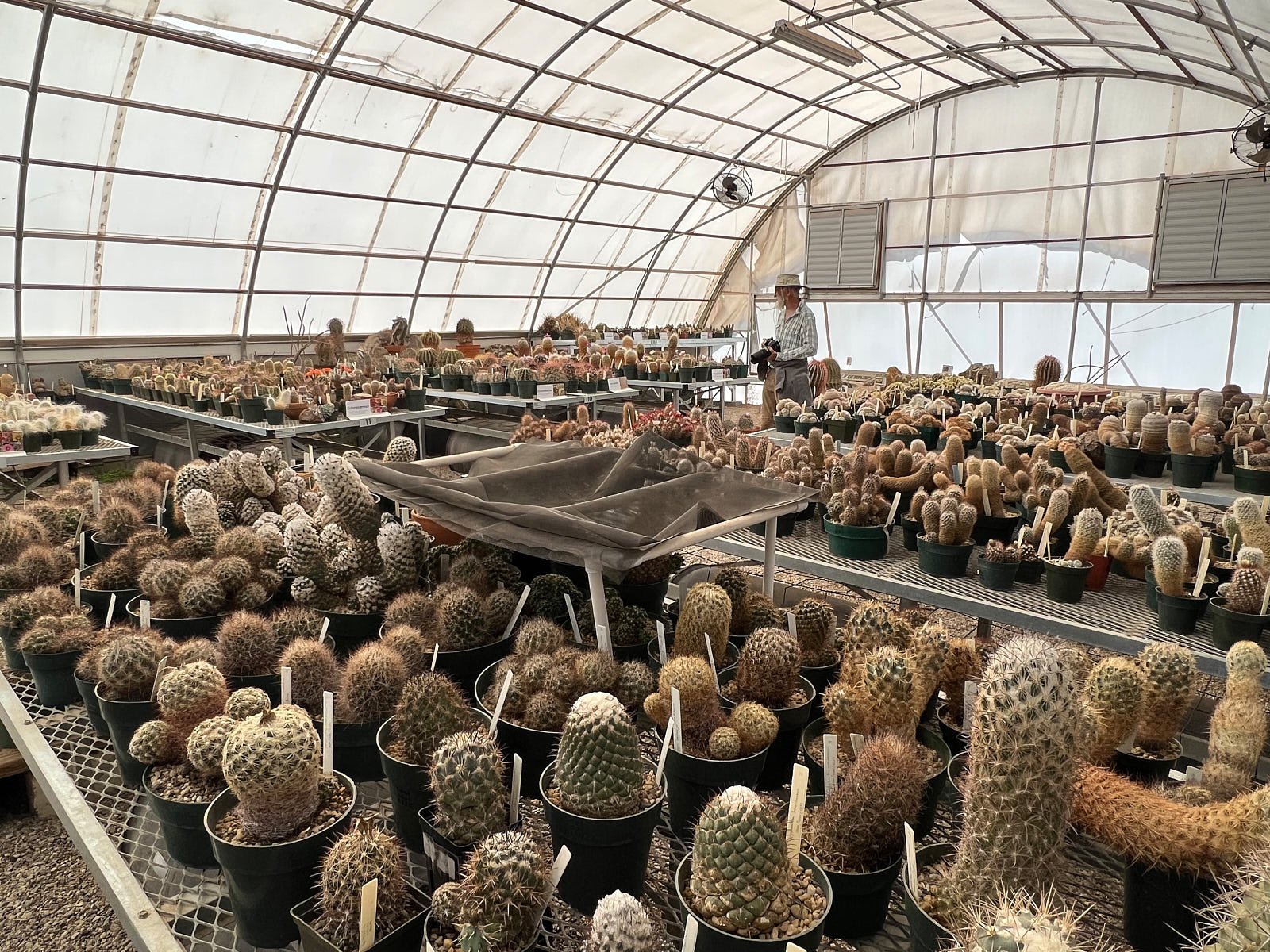

Cactus Garden, Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute.

Cactus Garden, Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute.

Both images: Cactus Garden, Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute.

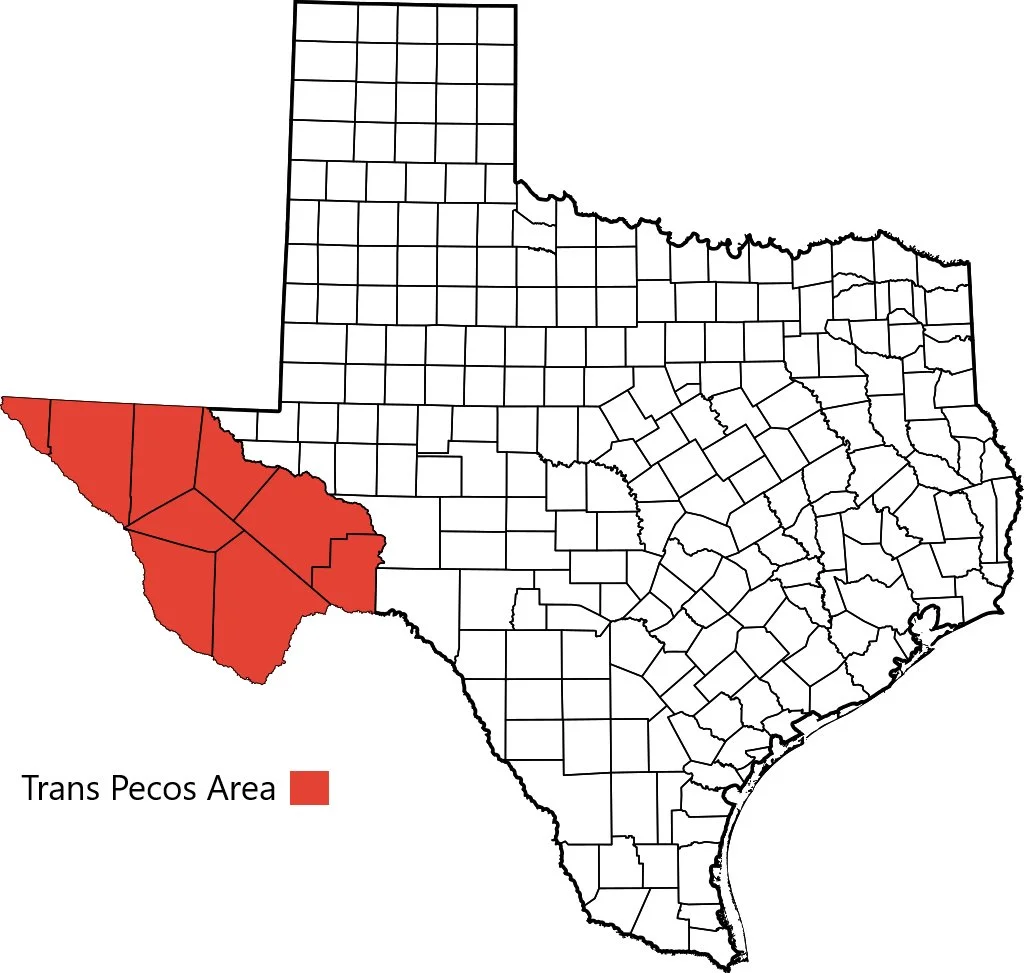

Trans-Pecos, Texas

From New Mexico, we journeyed south into the Trans-Pecos section of west Texas, exploring the attractive area around Fort Davis before pushing on to Big Bend National Park. The Trans-Pecos, as defined in 1887, is that portion of Texas that lies west of the Pecos River. It is the most mountainous and arid portion of the state and, apart from El Paso, is sparsely populated.

Magic Beans

It is our habit, when travelling, to break up periods of driving by stopping for coffee. This indulgence delivers the pharmacological benefits of caffeine, allows us to stretch our legs and experience a sliver of local life.

It has worked well for us - except in Texas. Every cup (no exaggeration) purchased was a disappointment. Not ice cold, not piping hot, just uninspiringly lukewarm muck. How to hurt a travelling man!

Fort Davis, Texas

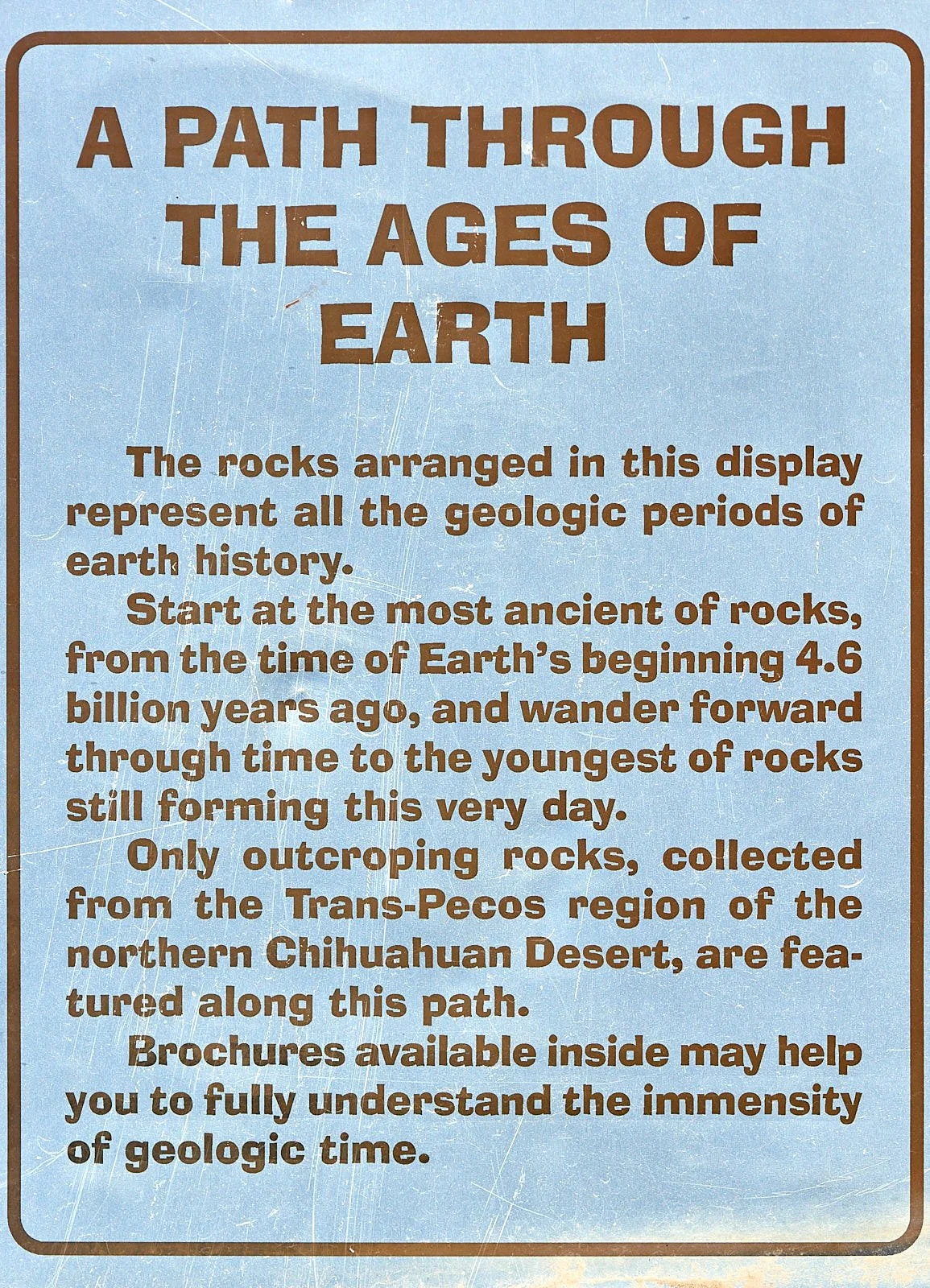

The area around Fort Davis provided us with a great introduction into the Chihuahuan Desert. Just a few miles from our Fort Davis accommodation is the Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute. The Institute promotes appreciation and concern for the natural diversity of the Chihuahuan Desert region. It’s native gardens and geologic interpretive displays have been thoughtfully planned and are outstanding.

Cactus garden, Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute

The cacti collection is truly amazing and should not be missed. It alone makes a visit worthwhile. All the species on display are found in the Chihuahuan Desert.

Davis Mountain State Park

Davis Mountain, a “sky island”, is a short drive from Fort Davis and includes a pleasant State Park.

We splashed out on a “full hook-up” campsite, meaning we had electricity and water connected to the Sportsmobile. Absolute luxury!

There is an information center, several hiking trails, two bird blinds and the University of Texas’ MacDonald Observatory nearby.

Non-native species

Late one afternoon, while hiking in Davis Mountain State Park, we spotted a Barbary Sheep (called “Aoudad” in this region); a species introduced to Texas in the last century for sport hunting. (Photo by Kuribo, Wikipedia)

Aoudads are native to North Africa. Being generalists in habitat and diet, they successfully outcompete the specialist, native, endangered Bighorn Sheep.

Over decades, Texans have developed an entire industry around hunting exotic animals such as Aoudads and selling exotic meats. The U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that ranchers in some parts of Texas generate more revenue raising exotics and white-tailed deer for hunting than they could raising cattle for beef.

We learnt that Texas had a significant number of exotic species, some of which have become very problematic (e.g.: Johnson grass, an Asian & N. African plant; Euroasian feral pigs – introduced in 16th century).

Sportsmobile buddies

Our motivation for visiting Big Bend was to link up with our friends B & T, and their travel friends C & E. We all own Sportsmobile vans and liberally congratulate each other on our excellent taste in three good things: camper vans, companions, and chilled wine.

B & T have ‘Sally’ – a Ford Transit, C & E drive a Mercedes Sprinter - and have ordered a newer version from Sportsmobile.

Our van remains unimaginatively nameless.

Primitive camp, Big Bend National Park.

Van with no name.

The stress is killing me.

Happy Hour

Croton Springs Primitive Site, Big Bend National Park.

Sunset happy hour was a special communal time. The skies transform, mountains soften under a red glow and the desert air cools to a perfect ambience.

We loved to hear our friend’s travel stories and to learn a little about their personal histories and experiences. What impressed us was their positive attitudes, open mindsets, excellent humor, and genuine appreciation for life’s bountiful opportunities.

Finding stars.

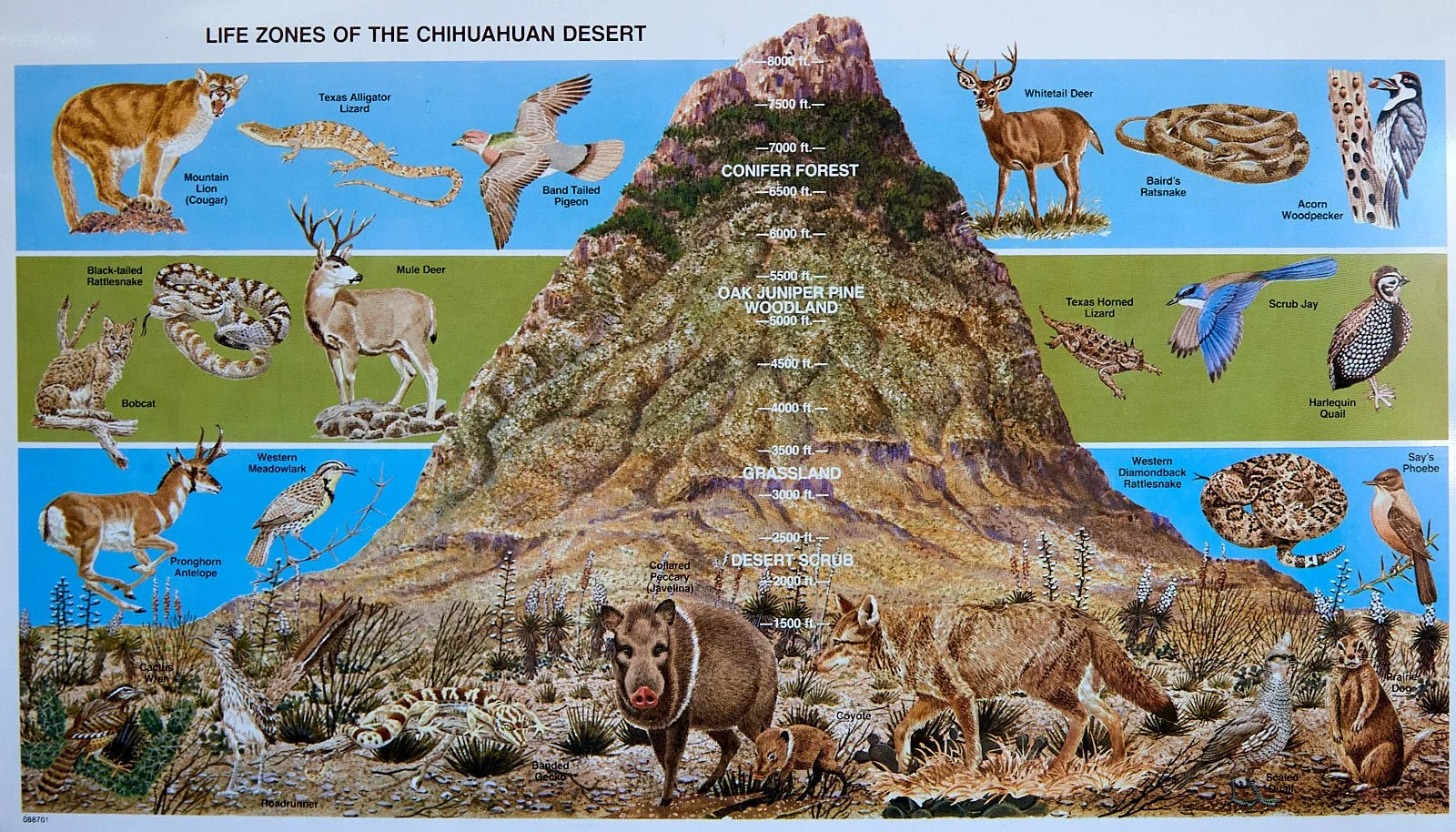

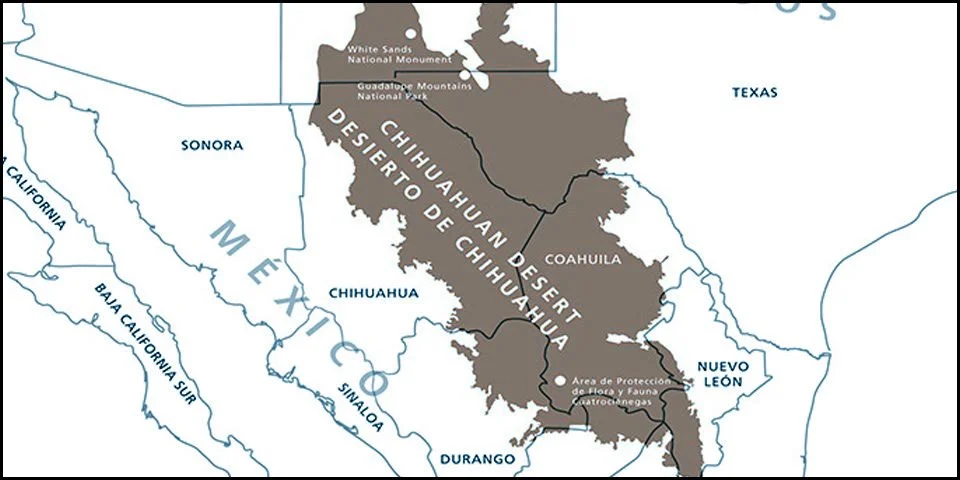

Chihuahuan Desert

Descending towards Big Bend National Park

The Chihuahuan Desert is the about 800 miles long and 250 miles wide. North America’s largest desert, it extends from the southern parts of E. Arizona, New Mexico and W. Texas down to the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt just 150 miles north of Mexico City.

It lies within a rain shadow. In Mexico it is bordered by the Sierra Madre Occidental on the west, which blocks Pacific rainstorms, and the Sierra Madre Oriental on the east, which blocks most storms from the Gulf of Mexico.

Most of the Chihuahuan Desert lies within Mexico.

Soil

Formed about 8,000 years ago – “young” in geologic time – , almost 80% of the desert consists of calcareous soils formed from beds of limestone when the area was beneath the sea. Sand and gravelly soils cover the desert flats, and debris from mountain erosion covers the bajadas.

Top row: Left - eroded limestone cliffs; Right - Chisos range, a sky island tall enough to capture moisture.

Middle row: Left - wind-eroded limestone; Right - Lechuguilla in the foreground, an agave species that is an indicator plant of the Chihuahuan Desert.

Bottom row: All images - desert soil and rock surfaces along a seasonal creek.

Vegetation

This primarily shrub desert is relatively green because much of it lies between 3,500-5,000 feet and receives more rainfall than other warm desert ecoregions. Also, the precipitation arrives when it is needed the most - during the hottest part of the year.

Left - typical desert shrub vegetation; Right - a Prickly Poppy variant. Usually the flowers are white.

Animals

The unusual confluence of extremes in elevation, precipitation, temperature and habitat types (high sky islands, complexes of small mountain ranges and valleys, and river floodplains) has produced enormous biodiversity that surpasses other North American deserts.

The Chihuahuan Desert hosts about 3,500 plant species, of which 1,000 are found nowhere else. It is a center for endemism of yuccas and cacti. The area supports more than 120 species of mammals, 300 species of birds, over 170 species of amphibians and reptiles, and 110 species of fish. Nearly half of the fish species are either endemic or of limited distribution and are found in isolated springs in closed basins. Humans have lived in the area since prehistoric times and will own responsibility for the region’s future because habitat loss and climate change are major concerns.

1st row: Left - Mound cactus spp (red flower) and Opuntia spp (yellow flower); Right - Probably bobcat tracks.

2nd row: Left - Collared Peccary (Javelina); Right - Big Bend Slider, a turtle that prefers ponds and rivers with muddy bottoms and aquatic vegetation.

3rd row: Left - Perhaps a Green Anole (brown form), a lizard species introduced into Big Bend National Park; Right - Buffalo pictograph.

4th row: Left - Flowing spring, laden with minerals that crystallize at the water’s edge; Right - Opuntia spp, plump with moisture.

5th row: Left - Opuntia spp flower; Right - Cholla spp new growth.

6th row: Left - Mound cactus spp flower; Right - Ocotillo in flower.

Close call

Since its discovery in 1926, the Big Bend gambusia has come perilously close to extinction several times. At one point, only three fish existed—Adam, Eve, and Steve . But these three fish produced numerous offspring that managed to survive and reproduce. Today, an estimated 20,000 descendants swim in three pools near Rio Grande Village.

Fish so fragile.

“This pond contains the world’s population of Gambusia gaigei. These minnow-sized fish have lived here since mastodons. Unique and fragile, they survive today only because man wants to make it so.” Seems a rather bombastic statement, given that the species was probably doing ok before mankind modified it’s habitat.

Big Bend National Park, Texas

When asked about Big Bend, Our friends B & T replied: “It is a place of extremes. You either love it, or hate it.” Turns out, we loved it.

Of course, we were lucky – it was a good year botanically. The park was verdant from the ample winter rains and cacti were in spectacular bloom. The topography is stark and the environment harsh, yet the Chihuahuan Desert supports an impressive diversity of life forms.

Rio Grande floodplain extending beyond low limestone hill.

Typical Chihuahuan Desert scrub

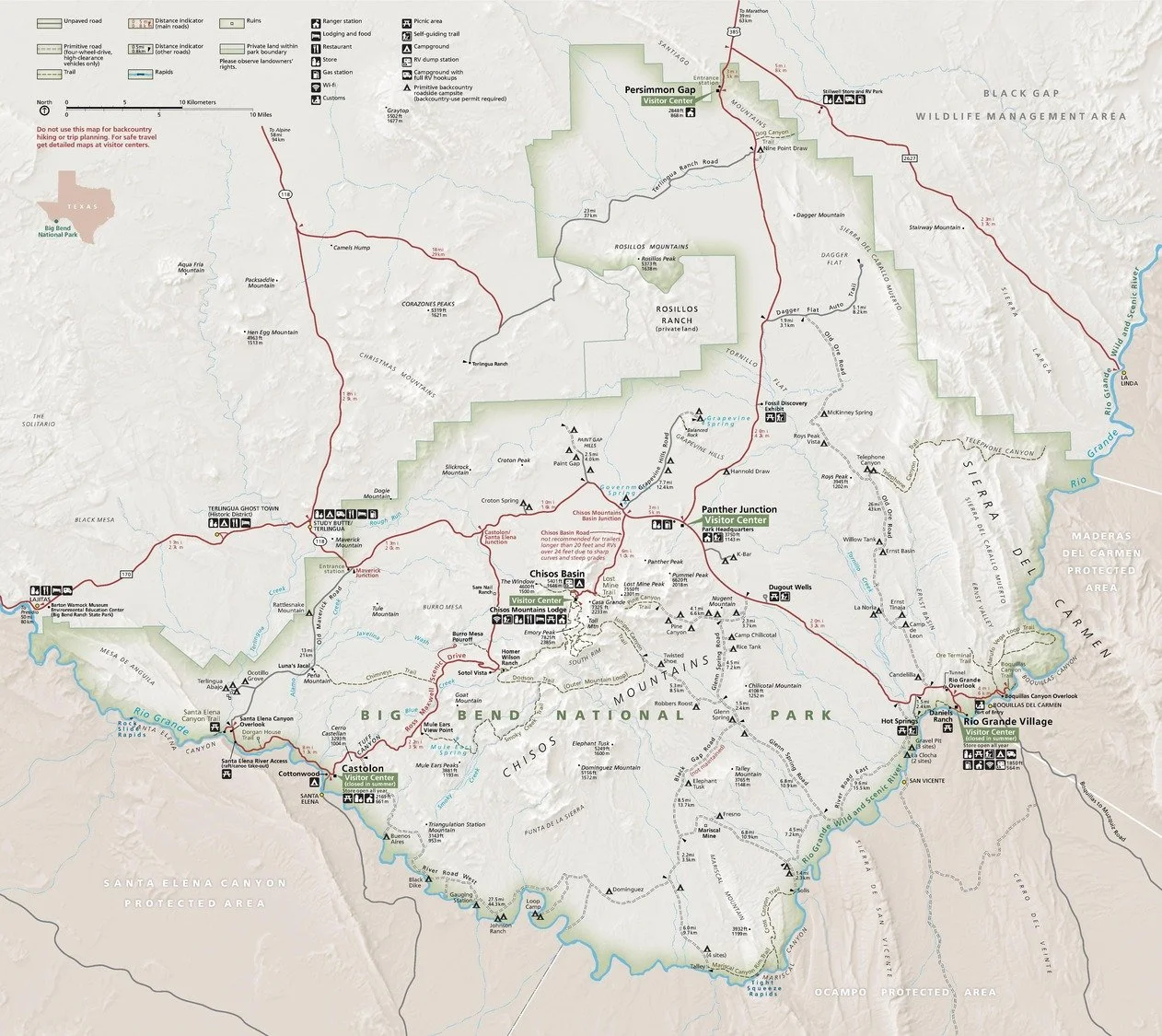

Big Bend Geography

The park lies at the southern limit of the Basin and Range physiographic province and at the northernmost limit of the Mexican Plateau, which lies between the two Sierra Madre Ranges (Occidental and Oriental). Elevations in the park range from 1,800 feet in the Rio Grande floodplain to 7,825 feet at Emory Peak in the Chisos Mountains.

Rainfall (“monsoon”) is mostly in summer and early fall. Scrub desert receives about 10 inches of rain, the Chisos Mountains average 18 inches and arid areas get <5 inches. June is the hottest month, with daytime temperatures >100°F. Nighttime temperatures often fall below freezing in winter.

Big Bend National Park brochure map

Big Bend Geology

Big Bend’s higher elevations are a mix of rocks from different ages. Younger ranges (40-60 million years ago) are an extension of the Rocky Mountains. The older ranges were uplifted 275-290 million years ago and are considered an ancient extension of the Appalachian Mountains. The Chisos Mountains resulted from volcanism about 32-38 million years ago and consist mainly of intrusive and extrusive igneous rock.

Chisos range: Views from various positions.

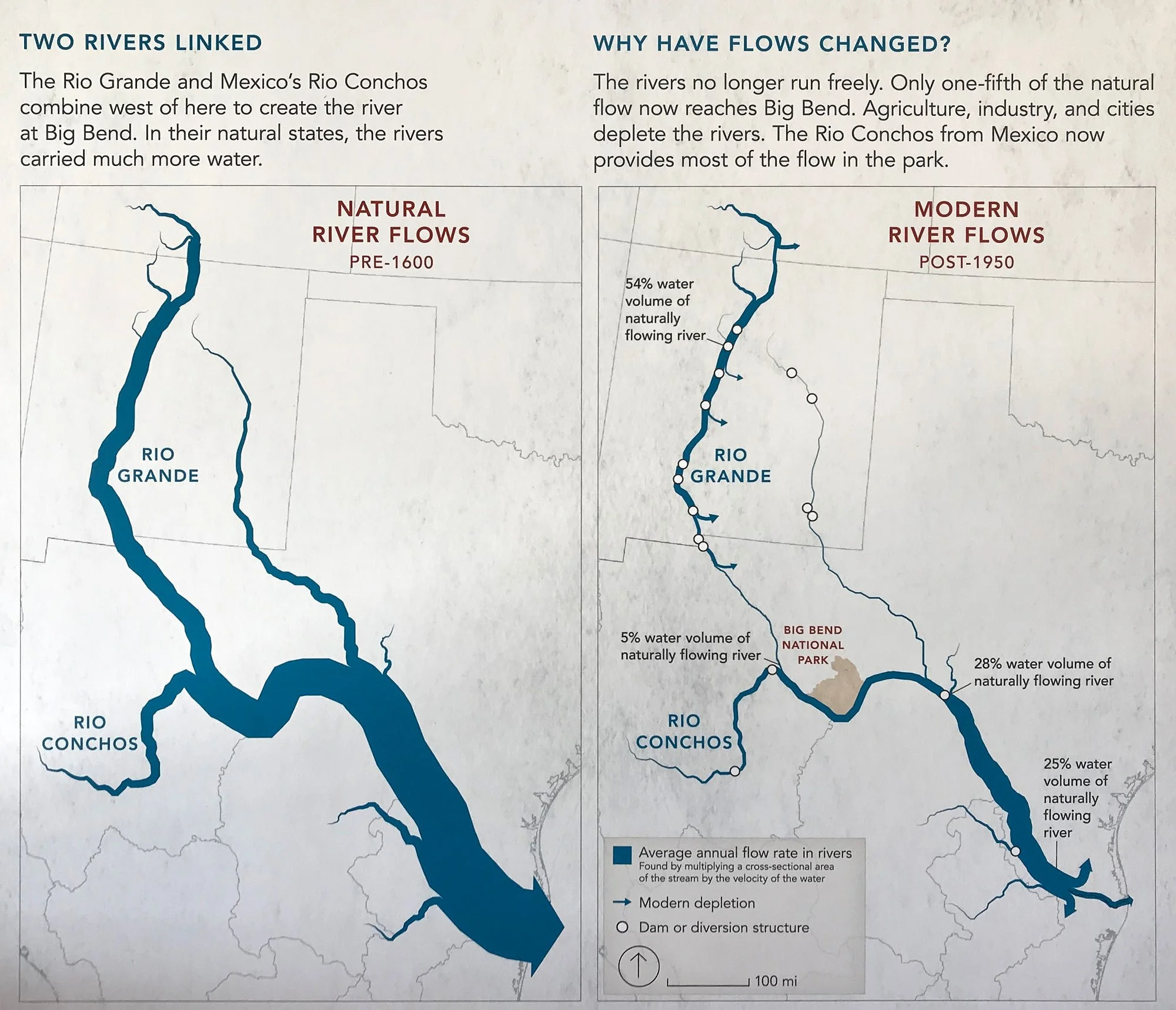

Rio Grande River

A Spanish cartographer, in 1536, was the first to depict the Rio Grande. The length of the Rio Grande is 1,896 miles, making it the 4th longest river in North America. It originates in south-central Colorado and flows to the Gulf of Mexico.

Over the ages, it has cut into underlying limestone to form several deep, narrow gorges that offer exciting river rafting opportunities. 260 miles of the river in New Mexico and Texas are designated as the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River.

Santa Elena Canyon

International boundary

The Rio Grande’s greatest depth is only 60 feet which has greatly curtailed its use for transportation. However, during the 19th century, more than 200 steamboats operated near the mouth of the river. Where we encountered the Rio Grande, it would be physically easy to cross over into Mexico. Mexican cattle and horses were often grazing within Big Bend National Park’s floodplain. Presumably, the international boundary shifts when the river’s course is modified by erosion, deposition and variations in river flow.

All images: Rio Grande

Cross-border commerce

Along the Park road to Boquillas Canyon Overlook, there was a neatly laid out display of Mexican curios for sale. No-one in attendance but a few bowls in which to place money. It provided a splash of tropical color to the Chihuahuan landscape and was a popular stop for visitors.

Water management

The river is an oasis and vital component of the Big Bend ecosystem. Since the mid–twentieth century, only 20 per cent of the Rio Grande's water reaches the Gulf of Mexico, because of the voluminous consumption of water required to irrigate farmland and to continually hydrate cities (e.g. Albuquerque). The water of the Rio Grande is over-appropriated: that is, more users for the water exist than water in the river. Because of both drought and overuse, the section from El Paso downstream through Ojinaga now frequently runs dry.

Wetlands

The meandering Rio Grande connects periodically to scattered marshes that offer refuge and sustenance to a variety of water-dependent creatures. The Park has constructed an aluminum bridge and floating deck to allow visitor access to ponds near the Rio Grande Village. It was nice to spend some quiet time by the water.

American coot feeding on aquatic plants

Black Phoebe hawking for insects

Camps

We camped at a developed campground (Rio Grande Village) and at remote sites that provide nothing more than bear-proof storage and a place to park. The latter offer solitude, the former has restrooms, potable water and shady cottonwoods. All the camping options offered good hiking and birding opportunities.

Rio Grande Village - a developed campground near a Parks interpretive center and a basic store with shower facilities. There are numerous nature trails to explore, including some to the Rio Grande and its associated riverine woodland and marshes.

Croton Spring trail is a lovely hike from a primitive camp. Keep an eye out for rattlesnakes - we nearly stood on one that stayed silent. There are four common rattlesnake species in Big Bend - Western Diamondback, Mojave, Black-tailed and Mottled Rock Rattlesnake.

Primitive camp

Some of our equipment was stolen from one of the remote camps. First time that’s happened to us in 30 years of USA camping. Was a jolt of unwelcome reality into our happy space.

Dawn chorus

In the desert scrub, bird activity was greatest in the early morning, while the night-time coolness still lingered and the sunlight is muted.

Black-throated Sparrow on ocotillo branch

Black-throated Sparrow

The Black-throated Sparrow is found throughout the southwestern United States and Mexico in arid upland habitats. A seedeater throughout the year, especially in winter, but during the breeding season often gleans insects from leaves and stems of shrubs. Black-throated Sparrow territories tend to be large during courtship and nest-building, shrinking to a smaller area around the nest while parents are incubating and caring for young. The male sings from high perches, while the female builds the nest low in desert shrubs or cactus.

(From: Birds of the World, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.)

Black-tailed Gnatcatcher

A “ zhee-zhee-zhee ” by the male first betrays the presence of this species; then, once spotted, a slender, minuscule bird is seen incessantly whipping its tail from side to side as it flits and darts around in desert thorn scrub in search of insects. The Black-tailed Gnatcatcher is is commonly found around dense thickets in the Desert Southwest. Weighing only 5 to 6 g, this gnatcatcher is among the smallest of North American songbirds.

(From: Birds of the World, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.)

Birding by the Rio Grande

The river’s woodland attracts a variety of bird species. Surprisingly, we encountered fewer neotropical migrants than elsewhere on our Southwest travels. We found Merlin, a phone app that identifies bird calls, to be incredibly useful, particularly when birding in an unfamiliar area.

Vermillion Flycatcher is common in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. It was breeding season and male Vermilion Flycatchers were performing their spectacular flight song above the tree canopy, appearing to bounce across the sky on fluttering wings while singing.

American Robin

Northern Cardinal (male) - “State bird” for Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia and West Virginia.

Northern Mockingbird

Turkey Vulture. Almost exclusively a scavenger, the bird's highly developed olfactory sense enable it to locate concealed carcasses beneath a forest canopy.

Bird interactions

The distribution of the Golden-fronted Woodpecker straddles the temperate and tropical regions of Middle America. In USA, it is only found in Texas and southwestern Oklahoma. The species nests in cavities excavated in live or dead trees, including mesquite and cottonwoods.

I was delighted to find a female occupying a potential nest site and kept my distance for a few days in order to minimize disturbance. However, the Golden-fronted Woodpecker seemed to lose interest in the cavity.

One evening, the reason became obvious - an Elf Owl had taken up residence.

Elf Owls often nest in old woodpecker holes. It is the world’s smallest owl species and feeds mainly on insects.

Javelina (Collared Peccary) enjoyed good grazing near Rio Grande Village campground

Looney Tune characters

There were two creatures that were somewhat tolerant of my camera and were an absolute joy to observe and photograph: Greater Roadrunner and Coyote.

Greater Roadrunner

This conspicuous but enigmatic terrestrial cuckoo of the American Southwest thrives in arid regions. An opportunistic predator, it feeds on snakes, lizards, spiders, scorpions, insects, birds, rodents, and bats, which it beats repeatedly against a hard substrate before consuming. During severe food shortages, it may eat its own young.

Greater Roadrunners are monogamous, maintain a long-term pair bond, and mutually defend a large, multipurpose territory. Each spring and summer, they renew their pair bond through a series of elaborate courtship displays in which the male bows and prances, wags his tail, and offers nesting material and food items to his attending mate. Both male and female incubate the eggs and feed and protect the young through a breeding season that lasts several months.

Historically, the Greater Roadrunner has been persecuted by ranchers and hunters who believe that it consumes the young and eggs of popular game bird species. Despite the persistence of illegal hunting, the Greater Roadrunner faces no serious declines in population numbers and continues to expand its range northward and eastward into new habitats.

(From: Birds of the World, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.)

Male

Female

Wile E. Coyote

I noticed this coyote dashing erratically around a tree in the grassy floodplain. It’s behavior made no sense at all.

It would stare intently into the tree canopy and then suddenly dart off to investigate something on the ground. There were ground squirrel holes in the vicinity but I was unsure of their relevance. Eventually I realized that the tree had berries which fruit-eating birds were eating. Birds are messy and some of the bounty would fall to the ground. Coyote would then take prompt possession of the goodies. Clever coyote!

Big Bend Vegetation

Five vegetation zones are described:

River floodplain (1,800-4,000 ft elevation)

Shrub desert (1,800-3,500 ft elevation)

Sotol-grassland (3,200-5,500 ft elevation)

Woodland (3,700-7,800 ft elevation)

Moist Chisos woodland (5,000-7,200 ft elevation)

Below are samples of the kaleidoscope of colors that we encountered while traveling through the landscape.

Information adapted from:

Bell, G.P., S. Yanoff, J. Karges, J. A. Montoya, S. Najera, A. Ma. Arango, and A.G. Sada. 2004. Conservation blueprint for the Chihuahuan Desert ecoregion. In: C.A. Hoyt & J. Karges (editors). Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium on the Natural Resources of the Chihuahuan Desert Region. October 14–17.

Little Big Bend, common, uncommon and rare plants of Big Bend National Park. R. Morley. 2008. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, TX.

Big Bend National Park web pages.