Connecting with friends: Pacific Northwest, June 2022

Selfie with Pacific Northwest friends

Bubble on wheels

After two years of Covid precautions, we felt compelled to connect face-to-face with our long-standing friends who live in Oregon and Washington State.

Vaccinated, double-boosted, armed with self-tests and isolated in the Sportsmobile, we headed north.

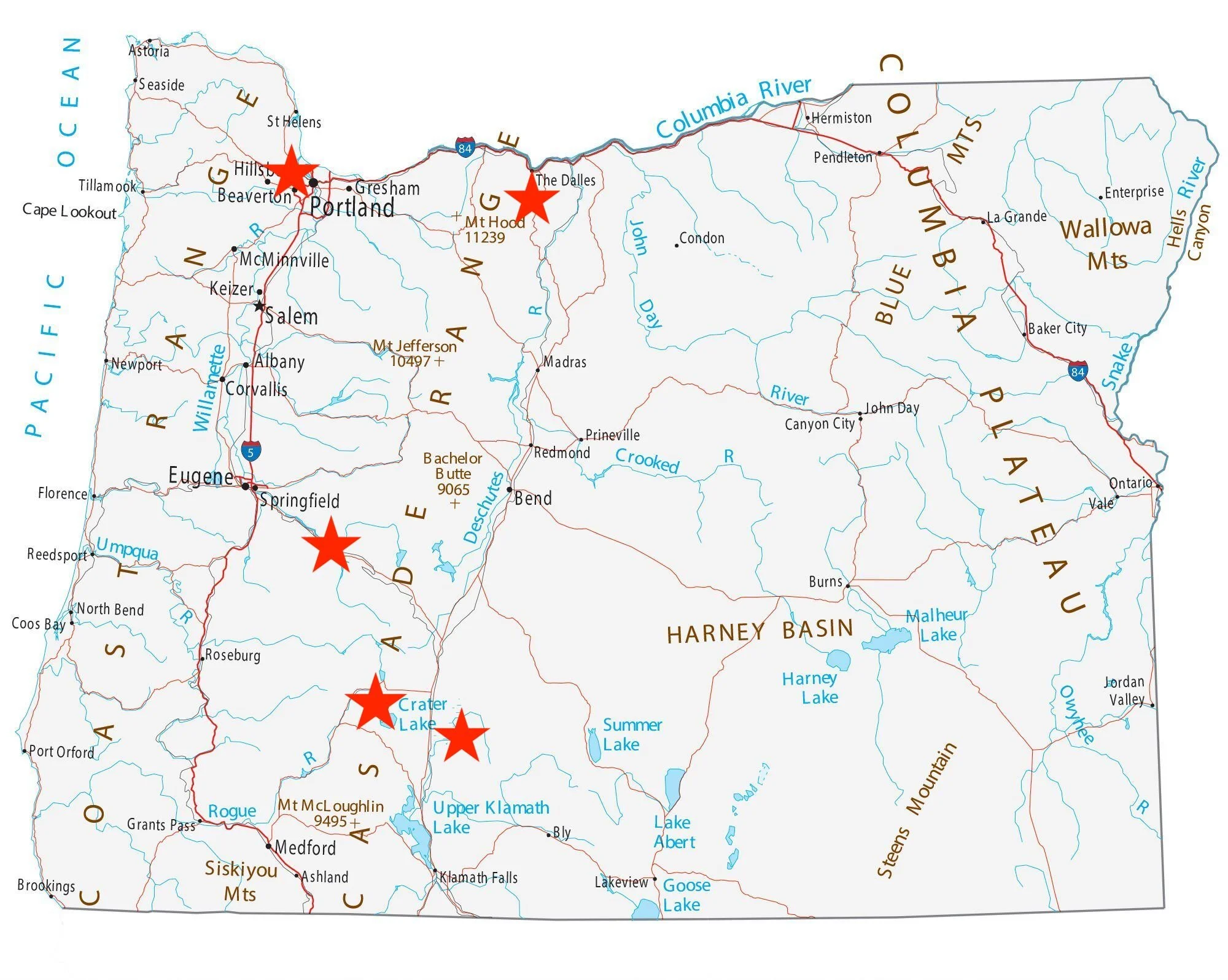

Our Route

We plotted an unhurried course using byways and National Forest roads whenever feasible. Red stars in the maps below indicated places where we stayed. Accommodation included designated campgrounds, dispersed sites and the luxury of friends’ homes in the Methow Valley, WA and Portland, OR.

Castle Crags

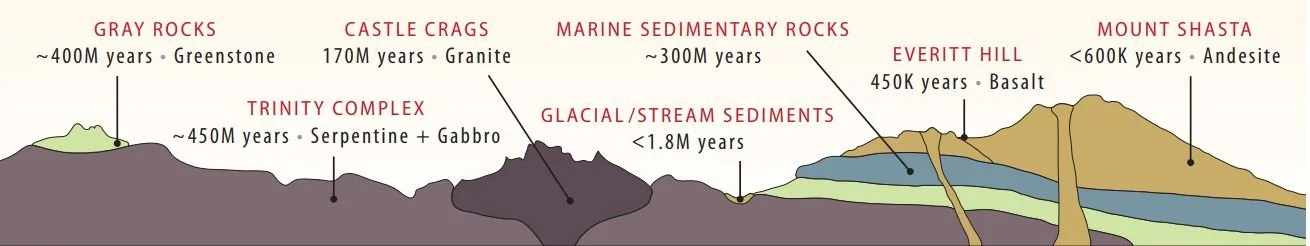

Castle Crags monolith and its surroundings provide a great introduction to the Klamath Mountains geomorphic province, which consists of multiple fragments of oceanic crust that have been added to the western edge of the North American continent by plate-tectonic processes. Rocks immediately surrounding Castle Crags consist mostly of Ordovician-aged (443–490 million year old) oceanic crust referred to as the Trinity ultramafic sheet. (See July 2021 blog for more on ultramafic rocks.) The spires and domes of Castle Crags are the result of an intrusion of granitic magma around 160 million years ago. Over time, the granitic pluton was exposed and shaped by erosion.

Cross-section of Castle Crags State Park region showing rock types. From: Castle Crags State Park 2014

Beyond the light-colored, erosion-resistant crags are hills with darker-colored, less-resistant ultramafic (peridotite and serpentine) and sedimentary rocks. Mount Shasta (a 14,162 ft volcano), is in the distance.

Left: Castle Crags granitic spires.

Right: Castle Crags Ivesia (Ivesia longibracteata) is a flowering plant in the rose family and is known only from Castle Crags.

Left: Sugarstick (Allotropa virgata) is among a unique group of species, referred to as the Monotropoideae, that do not have chlorophyll and are incapable of photosynthesis. These plants depend on root-associated fungi (mycorrhizae) to transport nutrients and carbohydrate to them from the roots of host trees such as conifers.

Right: Trail to Indian Springs.

The Cascade Range

The Cascades extend for over 700 miles from Mount Lassen in California, through Oregon and Washington, to southern British Columbia. The range captures moisture-laden westerly winds which results in heavy precipitation along its western slopes. Precipitation diminishes on the eastern slopes as the distance from the summit increases and the elevation decreases. On our journey north we travelled on the drier side of the Cascades and returned south via a more westerly, wetter route.

Mount Shasta viewed from the northeast, showing sagebrush and the aftermath of recent forest fires.

Jackson Creek, Fremont-Winema National Forest

We camped under ponderosa pines, near open meadows and a willow-lined stream.

The weather oscillated between sunshine and ominous storm clouds.

Two attentive American Robins were feeding a robust nestling that had fallen to the ground.

Top row, Left: Jackson Creek campground

2nd row: Grassland meadows. Picked up a few ticks while walking here.

3rd row, Left: Chickweed (Cerastium spp). Right: Strawberry spp.

4th row, Left: Claytonia spp. Right: Maianthemum spp.

5th row, Left: Buttercup spp. & Penstemon spp. Right: Buttercup spp.

6th row, Left: Rosy Pussytoes (Antennaria microphylla). Right: Prairie smoke (Geum triflorum).

Columbia River surprise

It rained solidly all day, so we pushed on to The Dalles by the Columbia River and enjoyed a Mexican meal. Driving to camp after dinner, we heard a prolonged squeal from under the hood. Oil everywhere - a seal in the vehicle’s power steering had failed. Next morning the van was towed to Precision Automotive who kindly adjusted their schedule to accomodate our repair. We checked in at a local hotel, visited an art center and sampled local brews at Clock Tower Ales while watching Steph Curry’s crew secure match #5 of the NBA finals.

Left: Hey, better than pushing the van into town. Right: The Dalles Art Center - a pretty sight.

Methow Valley

The upper end of Eastern Washington’s Methow Valley harbors four settlements - Twisp, Winthrop, Mazama and Carlton (listed in descending size). The area offers excellent winter and summer outdoor sport opportunities and is increasingly popular with internet-linked workers who have been liberated from office attendance by the pandemic.

Here we united with fine friends, some of whom had driven from Seattle for the occasion. Suffice to say it was wonderful to see everyone! Great company, good humor, excellent food, enjoyable activities and gracious hosts. A splendid gathering!

Locals remarked how green the countryside looked for this time of year. We heard the same in Oregon. Rivers were running high, warblers were singing and bears were out and about. Below is a sampling of Methow images.

Top row, Left: Paintbrush spp. & Lupine spp. Right: Lupine spp.

Bottom row, Left: Strawberry spp. Right: Mountain lady’s-slipper orchid (Cypripedium montanum).

Top row, Left: Elegant cat’s ears (Calochortus elegans). Right: Crab spider on Rosy Pussytoes.

2nd row, Left: Aster spp. Right: Spring growth.

3rd row, Left: Thimbleberry leaves. Right: Tweedy’s lewisia (Lewisiopsis tweedyii).

4th row, Left: Lupine spp. Right: Castellija spp.

5th row, Left: Phacelia spp. Right: Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus).

6th row, Left & Right: The Methow River was surging.

7th row, Left: Looking southwest over the Twisp River valley. Right: Douglas’ helianthella (Helianthella uniflora).

8th row, Left: Thimbleberry flower. Right: Agoseris spp.

9th row, Left: Tall silvercrown l (Cacaliopsis nardosmia). Right: Arnica spp.

Quiet moments

There were opportunities to spend a little time observing birdlife.

Top row, Left: Male Cassin’s Finch. Right: Female/immature Cassin’s Finch

Bottom row, Left & Right: Female/immature Cassin’s Finch

Top 4 rows: Male & immature/female Cassin’s Finch. This species is seen year round in coniferous forests of the mountainous West.

Bottom row, Left: Male Cassin’s Finch. Right: Male breeding American Goldfinch.

John Cassin (1813-1869) was a Philadelphia-based ornithologist who has five American birds named after him and four more from elsewhere in the world.

Guess who comes to the feeder…..

A Douglas squirrel.

All rows: Probably Western Tiger Swallowtail and Pale Tiger Swallowtail nectar feeding at Columbia lilies (Lilium columbium).

A young American Robin.

Out of the nest but not able to fly.

Left & Right: Juvenile/female Red Crossbill.

Crossbills are seed-eaters and the only birds in the world with truly crossed bills, a characteristic that allows them to bite and pry between the scales of conifer cones. At least 9 forms of Red Crossbills occur in US. They have differences in bill size and structure. In general, the larger & stouter-billed types forage most efficiently on larger and harder cones (pines); the smaller-billed types forage most efficiently on smaller and softer cones (spruces, firs, hemlocks). From: The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior.

Left: Pine Siskin. Right: Pygmy Nuthatch with insect

Chestnut-sided Warbler

This species winters in Central America and breeds in the north-east of North America. We were expertly guided to this bird by our Winthrop host. It is a rare sighting for the Methow Valley.

You can buy bird-friendly grown coffee that is named after this bird.

All rows: Male Rufous Hummingbird. This hummingbird species winters in Mexico and southwestern USA. It is renowned for having been recorded at the most northerly latitude of any hummingbird, vagrants having been found even on the western Alaskan islands.

Male Calliope Hummingbird - USA’s smallest hummer.

Cascade backroads in Washington

After ten delightful days in the Methow Valley, we turned south, heading to friends in Portland, OR. Traveling within the Cascades, we explored several areas immediately east of Rainier, St. Helens and Hood mountains. The region receives substantial precipitation; the snow-line was closer and the vegetation lusher than that seen during our drive north to Methow. Some of the unpaved, single lane logging roads required careful driving - perfect speed for roadside botanizing and birding! Took the time to enjoy day-hikes in Wenatchee, Gifford Pinchot & Hood National Forests, Goat Rocks Wilderness and Mount St. Helens National Monument.

Creek along Sculptured Rock trail near Swauk campground, Wenatchee National Forest.

Top row, Left: Fool’s huckleberry (Menziesia ferruginea). Right: Cedar.

2nd row, Left: Common camus lily (Camassia quamash). Right: Spotted coralroot orchid (Corallorrhiza maculata).

3rd row, Left: Maple leaf. Right: Sword fern.

4th row, Left: Mountain hemlock. Right: Douglas fir.

5th row, Left & Right: Scenery by Blue Pool campground, Willamette National Forest.

6th row, Left & Right: Scenery by Blue Pool campground, Willamette National Forest.

7th row, Left: Scenery by Blue Pool campground, Willamette National Forest. Right: Salal (Gaultheria shallon).

8th row, Left: Big leaf maple. Right: Herb Robert (Geranium robertianum).

9th row, Left: Lodgepole pine. Right: Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis).

10th row, Left: Blue Pool campground, Willamette National Forest. Right: Dispersed camp by logging road close to Dry Creek, Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

11th row, Left: Logging road near Clear Creek, Wenatchee National Forest. Right: Trilium (Trilium ovatum).

12th row, Left: Northern inside-out flower (Vancouveria hexandra). Right: Columbia windflower (Anemone deltoidea).

13th row, Left: Creek within Goat Rocks Wilderness. Right: Stream at North Fork Tieton River trailhead, Goat Rocks Wilderness.

14th row, Left: Common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale). Right: Madia spp.

Top row, Left: Clatonia spp. Right: Trifolium spp.

2nd row, Left: Sword fern. Right: Fir.

3rd row, Left: Bunchberry (Cornus unalaschkensis). Right: Sugar scoop (Tiarella trifoliata).

4th row, Left: Creek flowing into the Green River, St. Helens National Monument. Right: Twinflower (Linnaea borealis).

5th row, Left: Rusty saxifrage (Saxifraga ferruginea). Right: Pea spp.

6th row, Left: Thimbleberry. Right: Phantom orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae).

Oregon: fireworks - ancient & modern

We spent Independence weekend with good friends who were also work colleagues. Again, wonderful to reconnect in person! We were treated royally! Visited Portland’s exquisite Japanese Gardens, shopped at the Sunday produce market and strolled beside the Willamette river.

Attended a lovely neighborhood July 4th party that included an unfettered view of impressive fireworks.

Left: Song Sparrow. Right: Red-breasted Nuthatch. Both birds photographed at our hosts’ Portland garden

Volcanism in the Pacific Northwest

Similar to Washington, Oregon has ample evidence of past fiery explosions.

Columbia River basalt

Much of eastern Oregon is covered by lava flows of the Columbia River Basalt Group, most of which erupted about 15 million years ago. Basalt lava is relatively fluid and can flow over gentle topographical gradients.

Creation of the Columbia River Basalt is attributed the hot spot that now heats Yellowstone. The hot spot dwells within in the earth’s mantle and melts portions of the overriding continental lithosphere. As the lithosphere drifted west-southwest over the hot spot, a trail of volcanic features were created that became progressively younger as one approaches Yellowstone National Park.

Cascade volcanoes

The Cascades constitute part of the American Cordillera, an almost continuous sequence of mountain ranges that form the western "backbone" of North, Central and South America. The Cordillera is also the eastern half of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

Cascade Range volcanoes receive a relatively continuous supply of magma derived from the subduction of the Juan de Fuca Plate under the North American Plate. Moderately viscous lavas, such as andesite, tend to form the steeper stratovolcanoes such as Mt. Hood, Oregon’s highest mountain (11,239 feet). Most of the present volcano formed since about 500,000 years ago but beneath those lavas lie the remains of the Sandy Glacier Volcano, which dates back about 1.5 million years. Mt Hood’s recent eruptions include two major events, one about 1,500 years ago and one between 1781-1795, as well as two minor ones in 1859 and 1865.

Explosive eruptions tend to occur when the erupting magma is rich in water or carbon dioxide. The decrease in pressure experienced by magmas as they rise through the crust allows these compounds to become highly energized gases. If the magma is also highly viscous because a high silica content, the volcanic conduits can become plugged and the subsequent eruptions are extraordinarily violent, such as the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens.

Adapted from: Roadside Geology of Oregon, 2nd Ed, 2014. M.B. Miller. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, Montana.

Top row, Left: Mount Adams (12,281 ft elevation). Right: Goat Rocks information.

2nd row, Left: Mount Rainier (14,441 ft elevation). Right: Mount St. Helens (previously 9,677 ft and now 8,363 ft elevation)

3rd row, Left: Mount Hood view from Timberline Lodge. Right: Driving south towards Mount Hood (11,239 ft).

So, should we be worried?

There are 161 active volcanoes in the US. In its National Volcanic Threat Assessment, the US Geological Survey ranked 18 volcanoes as “very high” threats based on their eruptive history, recent activity and proximity to people.

Hawaii: Kilauea #1, Mauna Loa #16

Washington State: Mount St. Helens #2, Mount Ranier #3, Mount Baker #14, Glacier Peak #15

Alaska: Mount Redoubt #4, Akutan Peak #8, Makushin Volcano #9, Mount Spurr #10, Augustine Volcano #12

California: Mount Shasta #5, Lassen Peak #11, Long Valley Caldera #18

Oregon: Mount Hood #6, Three Sisters #7, Newberry Volcano #13, Crater Lake #17

Western slopes of Crater Lake

Volcano hazards

Tephra (rock fragments) and ash

Lava flows. Lava usually advances slowly but molten basalt that is confined within a channel on a steep slope can flow at 20 mph.

Lahars occur when hot gas, rocks, lava and debris mix with rainwater and melted ice and form a violent mudflow that can pour at 120 mph down a volcano’s slopes.

Volcanic gas - water vapor, carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide, hydrogen sulphide & toxic hydrogen halides (HF, HCl, HBr)

Pyroclastic flows are avalanches formed by hot gas, ash, lava & other volcanic matter. They typically travel at 50 mph or faster.

Volcanic landslides. A St. Helens landslide (5/18/1980) reached speeds of 100-180 mph and surged over a 1,300 ft. ridge located 3 miles from the volcano.

Crater Lake caldera with Wizard Island

Crater Lake

Crater Lake formed through the explosive eruption (about 50 times greater than Mt. St. Helens) and collapse of Mt. Mazama about 7,700 years ago. Crater Lake lavas are related to dacite and rhyolite which are very viscous. The eruption was so large that it emptied its magma chamber and the mountain collapsed into the void to form a deep caldera. Overtime, it was filled with rainwater and snow melt.

Wizard Island is the top of an andesitic volcano that erupted within a few hundred years after the caldera formed. Phantom ship is an outcrop of 400,000 year old andesite and is the oldest exposed rock in the caldera.

Adapted from: Roadside Geology of Oregon, 2nd Ed, 2014. M.B. Miller. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, Montana.

Phantom ship at Crater Lake

Looking west from Crater Lake, with mauve Phlox spp. and white Western pasque flowers (Anemone occidentalis) - also called tow-headed baby.

Left: Corn lily (Veratrum spp). Right: Vidae Falls by east rim road.

Volcanoes can affect climate

The most significant climate impacts from volcanic injections into the stratosphere come from the conversion of sulphur dioxide to fine sulphate aerosols. These increase the reflection of radiation from the sun back into space, cooling the earth’s lower atmosphere. Mount Pinatubo’s eruption on 6/15/1991 cooled the earth’s surface for 3 years, by as much as 1.3 degrees F.

Present day global volcanic carbon dioxide emissions constitute less than 1% of the carbon dioxide released currently by human activities.

Wisdom - Jane Goodall

Wisdom involves using our powerful intellect to recognize the consequences of our actions and to think of the well-being of the whole.

Unfortunately, we have lost the long-term perspective and we are suffering from an absurd and very unwise belief that there can be unlimited economic development on a planet of finite natural resources, focusing on short-term results or profits at the expense of long-term interests.

The hallmark of wisdom is asking, ‘What effects will the decision I make today have on future generations? On the health of the planet?’

The Book of Hope, Jane Goodall & Douglas Abrams, 2021.

Home again - feeders to fill

Sugar (by John Kooistra)

Hummingbirds too fast to count

hustle flowers

and flit through my air space

where I flinch again

and laugh.

Everyone gets something

from this performance.

Entertainment for me,

sustenance for the hummers,

and pollination for the blossoms

dressed in red

like single women at the bar.

Male Anna’s Hummingbird. If you are want to know more about hummers, check out this book.