The Colorado River & Sonoran Desert: February 2022

Ocotillo, Anza Borrego State Park

“Plans to protect air and water, wilderness and wildlife are in fact plans to protect man.”

Stewart Udall (US Secretary of the Interior, 1961 to 1969)

Thorns & Water - Sonoran Desert habitats in California’s lower Colorado River region & Anza Borrego Desert Park

After a six-month hiatus in travel for home repairs, we ventured south to the Lower Colorado River, intrigued by the contrasting environments of a celebrated river flowing through harsh Sonoran Desert.

Wind Wolves Preserve

Our first stop, Wind Wolves Preserve, is an interesting convergence of valley, montane, desert and coastal influences. It is managed by the Wildlands Conservancy whose goal is “Preservation for Beauty and Biodiversity”, with an emphasis on environmental education of children.

They have made substantial efforts to restore habitat – including native plantings, removal of non-native vegetation, elk re-introduction and grazing rotation using cattle & sheep. Public outreach is impressive, signage is excellent & facilities are free.

You can learn more HERE.

Bakersfield cactus (Opuntia basilaris var. treleasei) is a California endangered species that the Preserve is successfully propagating.

The campground has a small stream running through it.

Blue Dicks were blooming when we hiked San Emigdio Canyon.

Back at camp, we made acquaintance with some of the neighborhood inhabitants - Acorn woodpecker, California ground squirrel, Red-tailed hawk, Song sparrow. Enjoyed a splendid after-dinner sunset.

Great After-Sales Service

A strut supporting our Sportsmobile poptop broke along a weld, probably the late consequence of a 2021 operating error.

We detoured to Fresno and Sportsmobile West (now Field Van) promptly fixed the problem.

Very kind of them to accommodate us in their busy schedule!

Cibola National Wildlife Refuge

“We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” Aldo Leopold (1887-1948)

Cibola National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1964 as mitigation for the straightening, channelization, and armoring of the banks of the Colorado River by the Bureau of Reclamation to prevent flooding. The purpose of the 18,444-acre refuge is to protect and recreate the marshes, backwaters and meanders that natural flooding would have formed and which provided wintering grounds for migratory waterfowl and other wildlife.

We birded the Cottonwood-lined marshes and found American Wigeon. Unfortunately, we had to cut short our time at Cibola. It merits a re-visit.

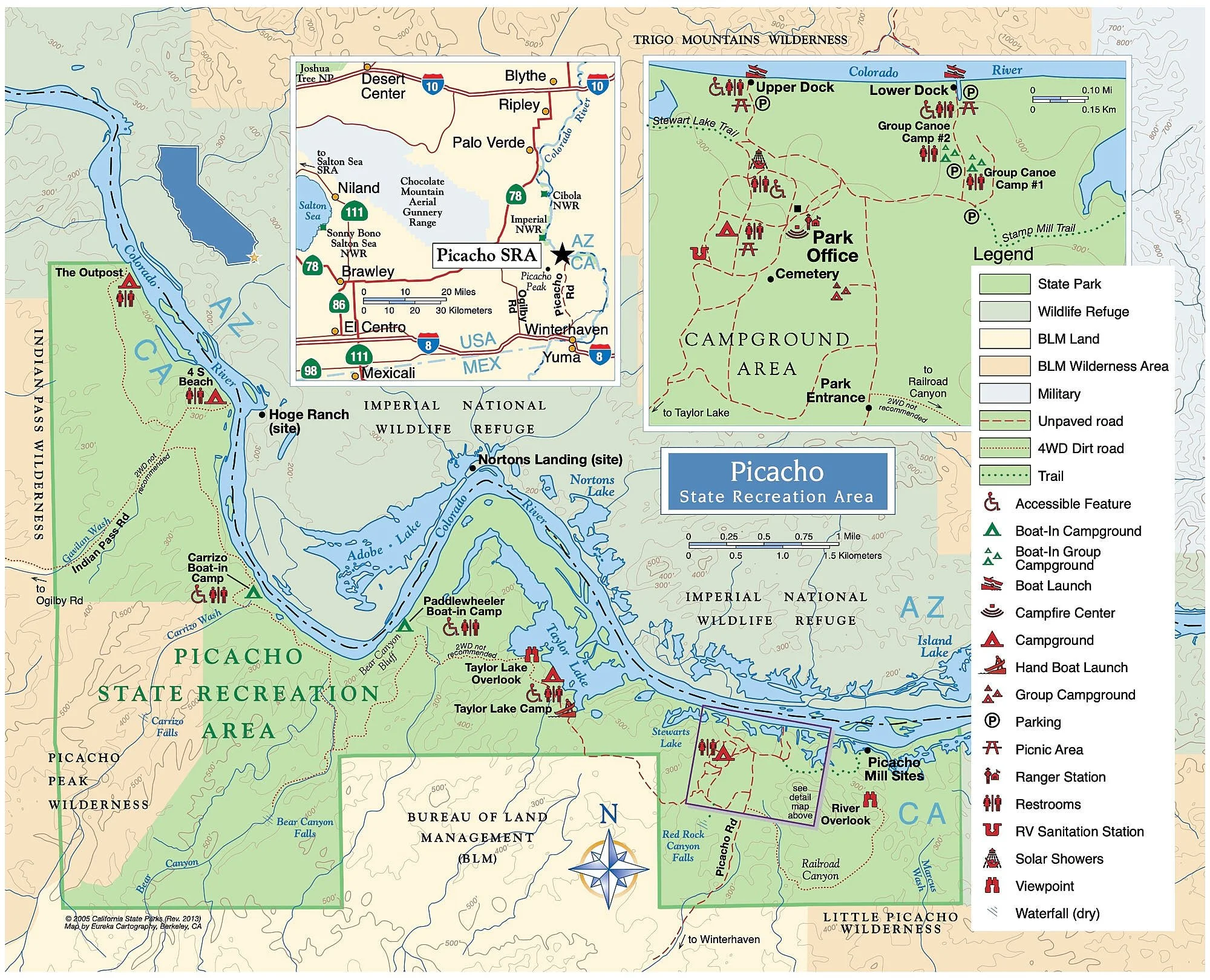

Picacho State Recreation Area

Left Interstate 8 at Winterhaven and travelled 18 miles along a rough dirt road that will deter most casual visitors in low clearance vehicles. Camped at Taylor Lake .

The Great-tailed Grackle was a regular camp visitor.

More about Picacho SRA HERE.

Kayaking on the Colorado

We accessed the Colorado via Taylor Lake’s reed-lined inlet and paddled upstream in our inflatable 2-person kayak, aiming for Paddlewheeler boat-in camp if the current proved manageable. Took about 2 hrs to get there. The downstream journey took half as long and we hardly paddled. Current was about 5mph.

Colorado River ecology

Originating high in the Rocky Mountains, the Colorado River drains parts of 7 U.S. States, Baja California and Sonora, Mexico. It provides water for about 40 million people, about one-third of whom actually live in the river basin. The Colorado River’s waters rarely reach the Sea of Cortez because the legal allotment of water to U.S. and Mexico exceeds what the river can deliver. No water was reserved for conservation needs.

In the last century, massive dams were created that eliminated the natural seasonal changes in flow and water temperature that fashioned the evolution of native fish species. Overall, human modification and stabilization of rivers and construction of reservoirs allowed exotic fish fauna to become established and flourish. Native species are greatly depleted.

The Colorado River today is more akin to a man-made plumbing system than a wild, naturally flowing river. Even in areas where the water’s course is not constrained by concrete, the riverine habitat appeared depleted – diminished biodiversity.

Adapted from: Craig C. Ivanyi & Paul C. Marsh. A natural history of the Sonoran Desert. 2nd Ed. 2015.

To my African eyes, the lower Colorado cannot match the natural richness of the lower Zambezi.

Anza Borrego Desert State Park

After at visit to Yuma for fuel and coffee, we drove west to Borrego Springs, a hamlet within the State Park. En route, we visited Yuha Desert Natural Area which protects the Crucifixion Thorn (Castela emoryi), a desert-adapted bush that is rare in California. It seldom has leaves; photosynthesis is performed in the intricately branched stems. Storm clouds gathered during the journey and we had the unusual desert experience of rain, with snow adorning the higher ranges.

Temperatures plummeted but fortunately we had planned two days in a hotel to celebrate our 30th wedding anniversary and restock with supplies.

Nolima Wash

After a binge of Mexican food and fun shopping (glass art, Panama hat), we relocated to Nolima Wash and then Mine Wash - areas that we had enjoyed on a previous trip.

The Sonoran Desert in the lower Colorado River region is particularly arid and this season’s rainfall was less than normal. Therefore, we expected very few annual wildflowers. However, the textured landscape is beautiful and ocotillo, desert lavender, chuparosa and several cacti species were blooming.

CAM photosynthesis

Photosynthesis allows plants to utilize solar radiation & an enzyme called Rubisco to convert water and carbon dioxide into storable energy (sugar and starch) that is used for maintenance and growth. The leaves and stems of terrestrial plants have stomata (pores) that permit carbon dioxide to enter the plant. However, water vapor can exit via open stomata which is problematic for plants in arid environments. Most plant species (>90%) photosynthesize during the day when their stomata are open – C3 photosynthesis. C3 is the oldest photosynthetic pathway, originating around 2,800 million years ago.

Cacti and many other succulents keep their stomata closed during the day to conserve water & open them at night to take in carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide is enzymatically converted to malate and stored within the plant in large central vacuoles until daytime. When sunshine arrives, carbon dioxide is released from malate and photosynthesis occurs. This process is called CAM photosynthesis.

CAM photosynthesis is found in about 7% of vascular plant species and has evolved independently several times. CAM plants are found in arid habitats (e.g.: cacti, cholla, yucca) and in tropical epiphytes that have sporadic water availability (e.g.: orchids and bromeliads). A disadvantage for CAM plants is that they often have low photosynthetic capacity, slow growth, and low competitive abilities because their photosynthetic rates are limited by vacuolar storage capacity and by greater cellular energy costs. However, there is great plasticity in the expression of CAM photosynthesis. Many CAM plants can function in a C3 mode with stomata open during the day when water is available, so low photosynthetic and growth rates are not always limiting factors.

Look HERE for information on C4 photosynthesis.

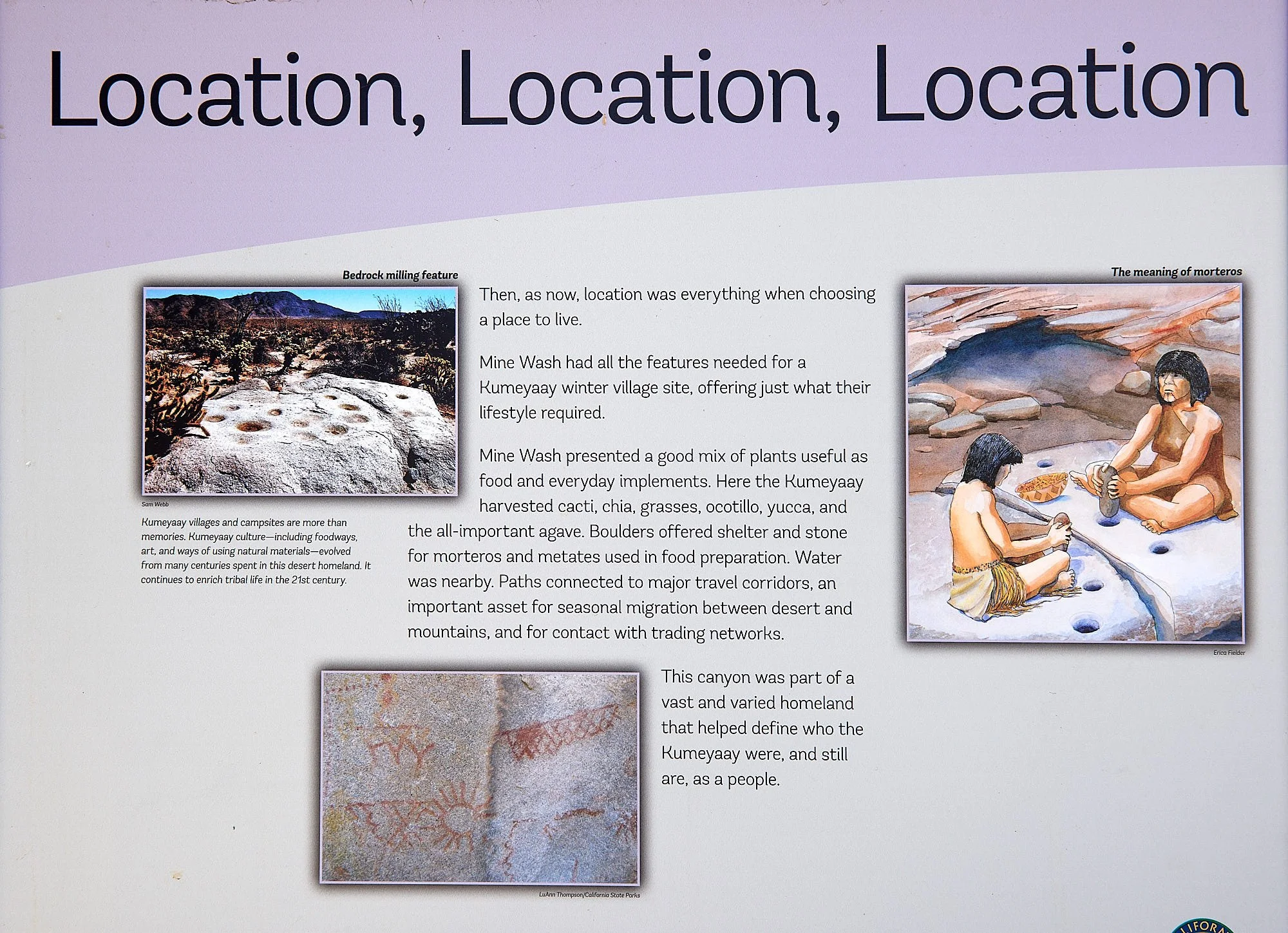

Kumeyaay village site at Mine Wash

Prior to European contact, the Kumeyaay lived in Sh’mulq (clan) territories with summer and winter village sites. The Kumeyaay practiced a sophisticated form of environmental management. Fire was used to open up land where chaparral vegetation was dominant. In the drier areas approaching the desert, drainages were dammed using rocks and brush to trap sediment. This helped to raise the water table and allowed the creation of wetlands.

The harvest of resources was done according to rules established from centuries of learning. The timing of the harvest could be by celestial observation or through the use of an unrelated "indicator" species. Some plants had a wide range of harvest time but were known to be more tasty during certain periods of their development. An example of this type of plant is Yucca, which becomes bitter after blooming.

Information from https://www.kumeyaay.com

Conserving Biodiversity

“Conservation is emphatically not about “saving the planet”. From the perspective of deep time, we humans can’t “destroy the planet” in any significant way. The greatest damage we could do would heal in a few million years; a different, self-sustaining, ecosystem would evolve. But we can easily alter the global ecosystem to the extent that it will no longer support human life.”

Mark Dimmitt & Margaret Fusari. A natural history of the Sonoran Desert. 2ndEd. 2015

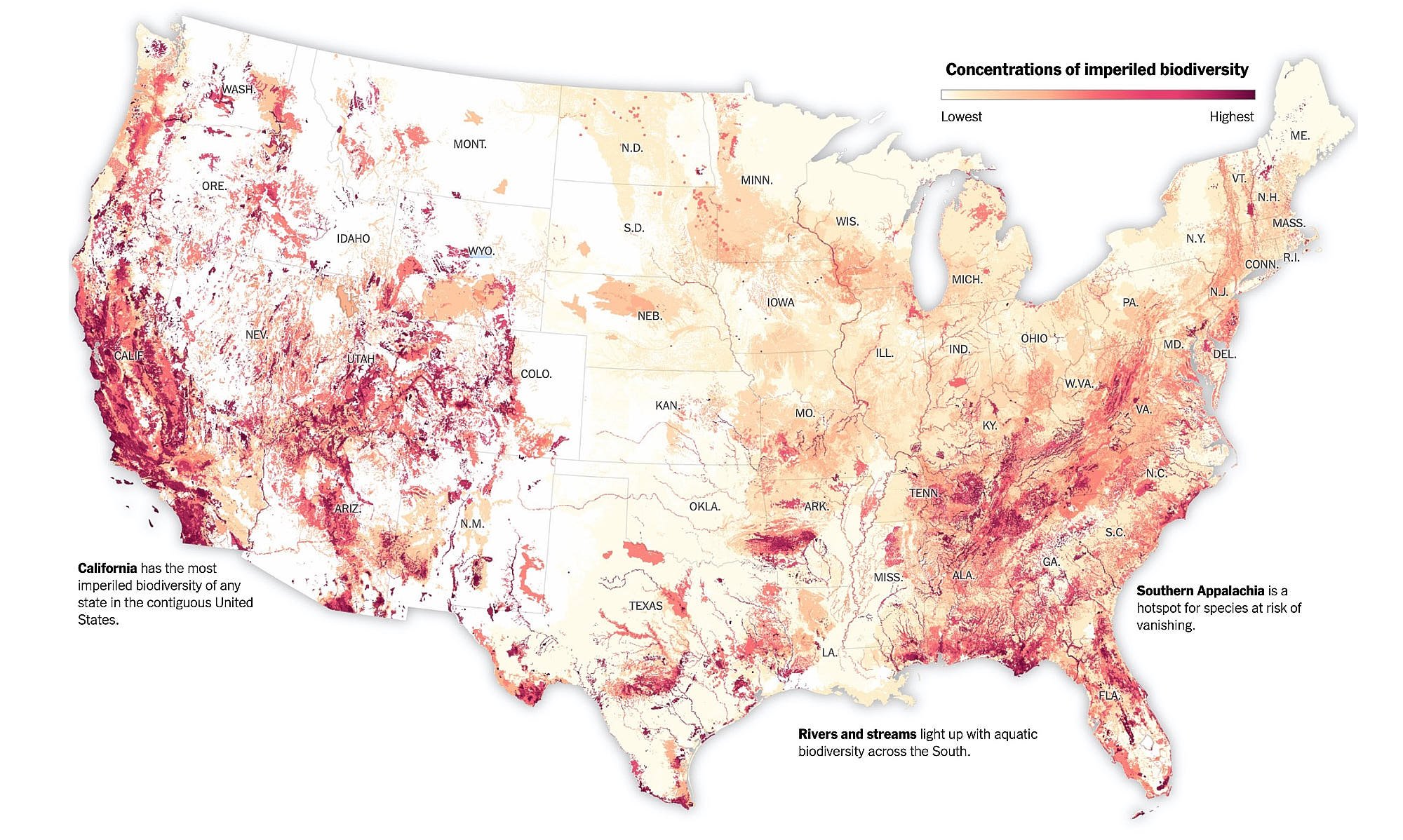

New York Times, March 3, 2022

The red areas are the places in the lower 48 United States most likely to have plants and animals at high risk of global extinction. Maps like these offer a valuable tool for protecting biodiversity.

A new United Nations assessment has concluded that humans are transforming Earth’s natural landscapes so dramatically that as many as one million plant and animal species are now at risk of extinction, posing a dire threat to ecosystems that people all over the world depend on for their survival.

Human activities have resulted in extinction rates that are currently tens to hundreds of times higher than they have been in the past 10 million years. In most major land habitats the average abundance of native plant and animal life has fallen by 20 percent or more, mainly over the past century.

At the same time, a new threat has emerged: Global warming has become a major driver of wildlife decline by shifting or shrinking the local climates that many mammals, birds, insects, fish and plants evolved to survive in. When combined with the other ways humans are damaging the environment, climate change is now pushing a growing number of species closer to extinction.

Trip Reflections

Both the Colorado River and Sonoran Desert ecosystems have been adversely impacted by human activities and provide lessons we could apply going forward.

At a time when the world’s nations should be actively addressing global warming and mass extinctions, we have Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. There will be enormous diversion of resources and effort, perhaps even the use of nuclear weapons. It is hard to believe that Homo sapiens will save itself.