Chasing the Southwest Monsoon: September & October, 2023

Section #4: Southwest History.

Nine Point Draw, Big Bend, Texas.

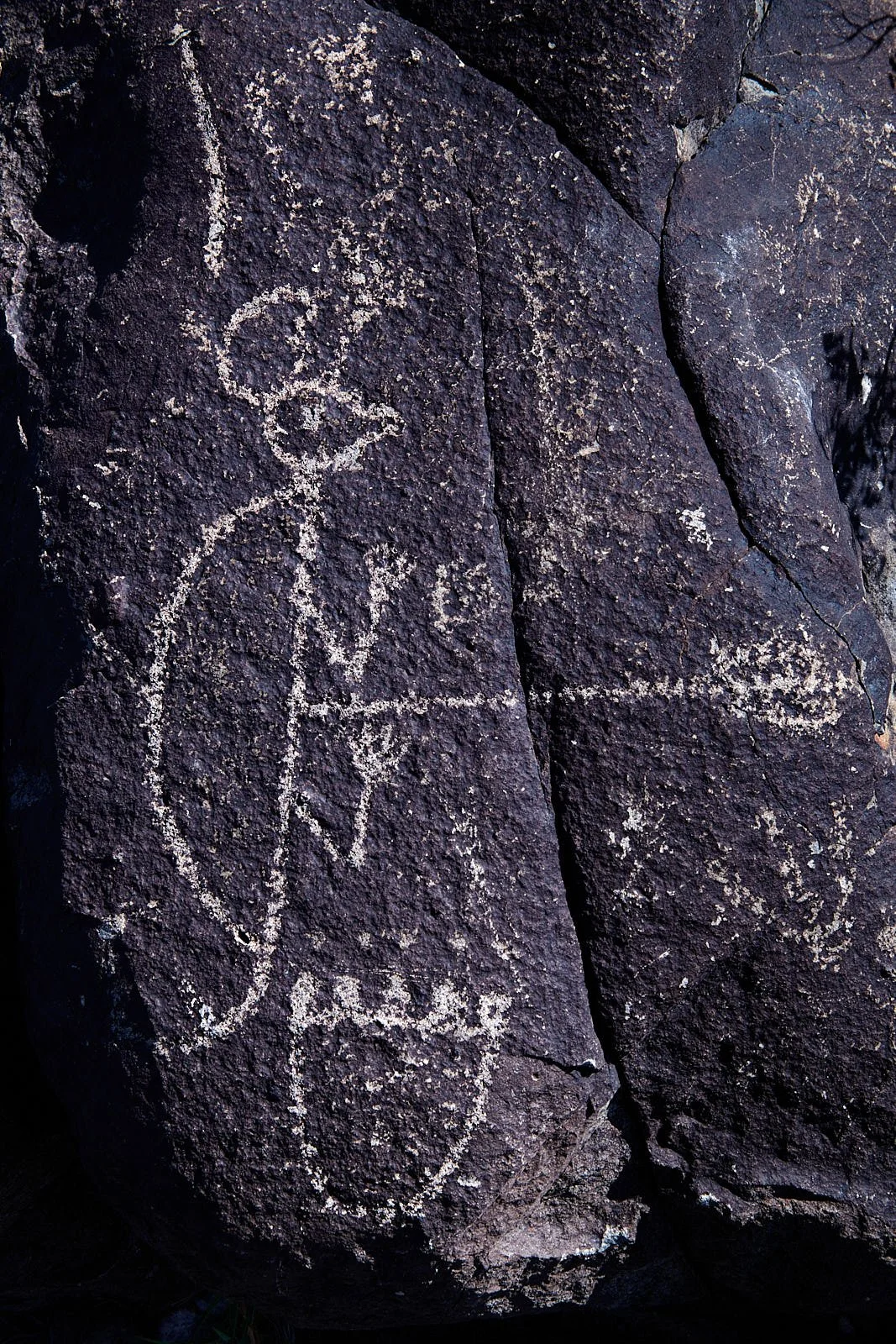

Three Rivers Petroglyph Site, New Mexico.

White-winged Dove awaiting dawn.

“Preserving our archeological heritage: In the long run, education is probably the most effective approach.”

David Grant Noble

Davis Mountains State Park, Texas.

Northern Flicker

Sacramento Mountains, New Mexico.

Walker Creek, Arizona

Ancient Cultures

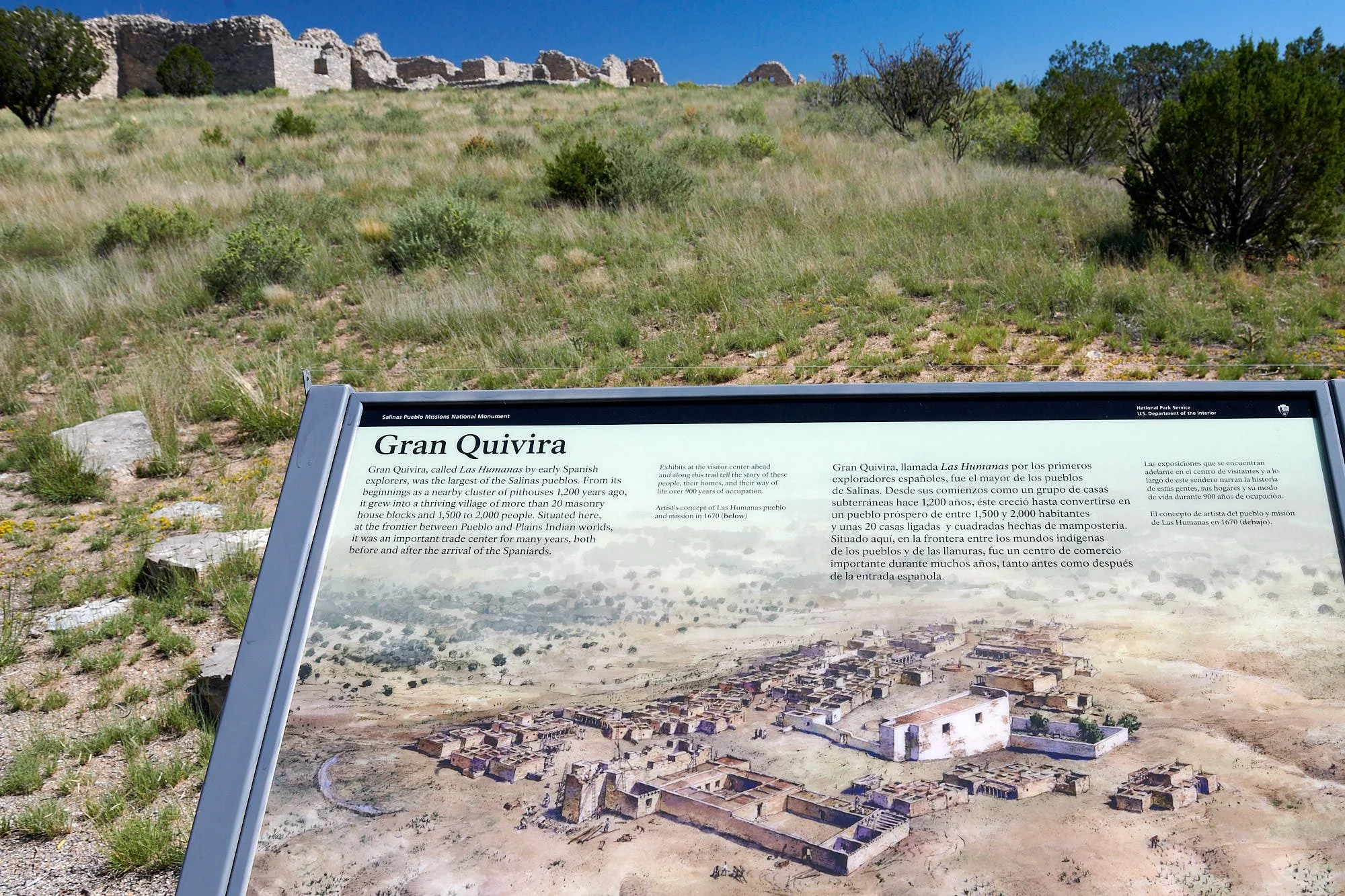

Several ancient ruins were visited during our wanderings, including Chimney Rock, Bandelier National Monument, Gran Quivira, Gila Cliff dwellings and Montezuma Castle.

The term “Paleo-Indians” refers to the first peoples who entered and subsequently inhabited the Americas during the final glacial episodes of the late Pleistocene period. Their population densities were quite low.

Paleo-Indian megafauna hunters roamed extensively, as evidenced by the wide-spread occurrence of the Clovis spear point in North America.

Left: Rock art at Three Rivers Petroglyph Site. Right: Points at Mimbres archeological site.

Ancestral Pueblo

In the Southwest, the Paleo-Indian period transitions to the Archaic around 8,000-7,000 BCE (Before Common Era) and Archaic period extends to approximately 200 CE. Archaic Indians hunted less big game (ate a lot of rabbits) and spent more time gathering plants, adjusting their activities to optimize harvesting of plant foods.

Archaic people, in the later period, were starting to live in permanent villages, travel less extensively, and develop the technologies of pottery, weaving, and agriculture.

Top row, both images: Displays at Montezuma Castle, Arizona.

Bottom row, left to right: Artifacts displayed at Bandelier National Monument, NM; Chimney Rock National Monument, CO; Mimbres Museum, Silver City, NM.

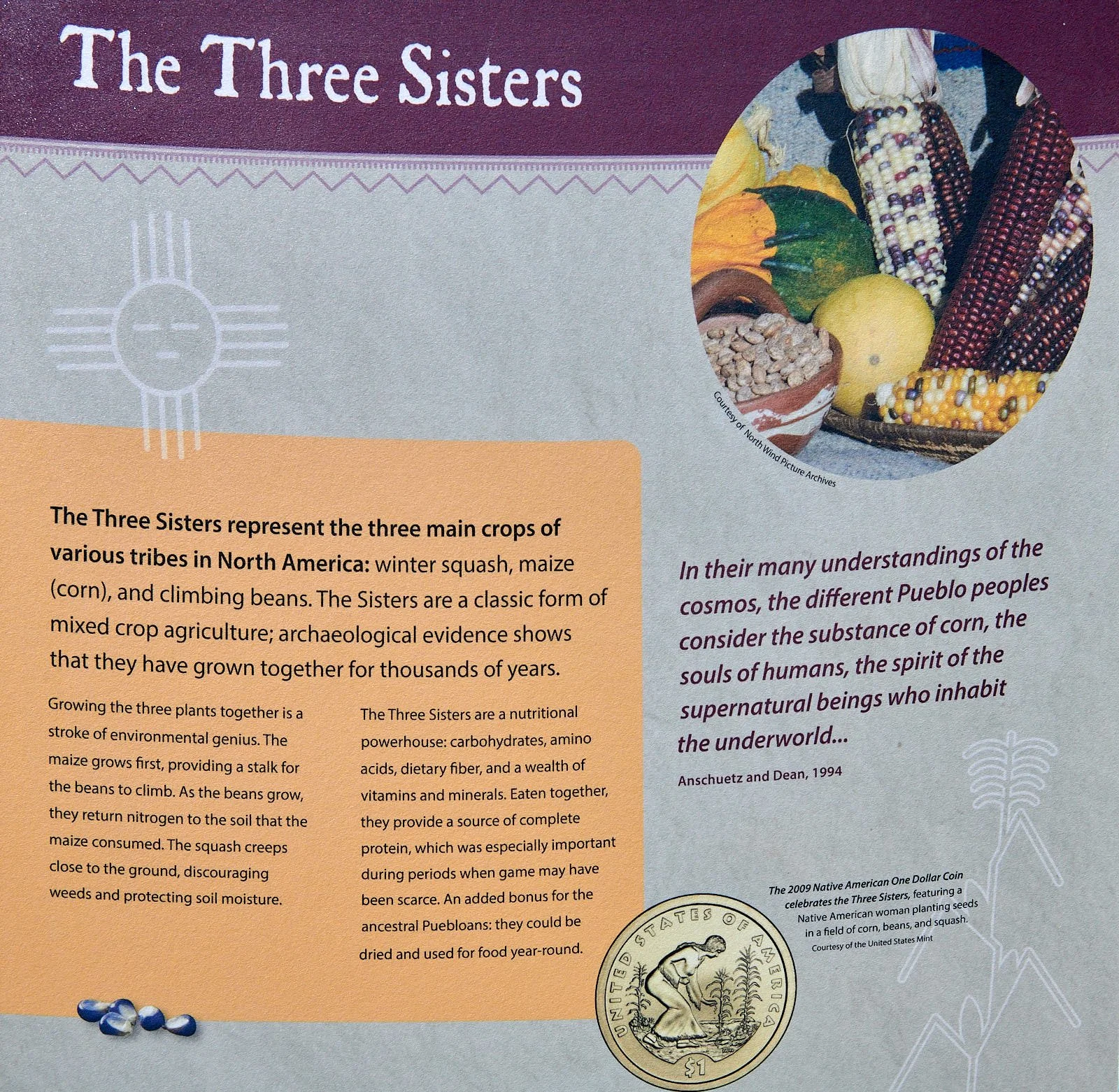

Agriculture

Corn and squash were domesticated in the Mexican highlands approximately 4,500-4,000 BCE and were introduced to the Southwest by 2,000 BCE. Beans were initially domesticated in Mexico circa 200 BCE.

Around 500 CE, Southwest farmers starting planting beans with corn and squash. The crop triad is referred to as the “Three Sisters”.

Corn has tall, sturdy stalks that beans can climb. Beans have root nodules that capture nitrogen and return it to the soil as fertilizer. Squash spread near the ground, offering shade, retaining soil moisture, inhibiting weed invasion and deterring herbivores with its prickly leaves. Also, beans contain lysine, an essential amino acid that the other two crops lack. Lysine is required by humans for protein production and other cellular processes. Meat contains lysine.

Display at Chimney Rock National Monument, Colorado.

Gran Quivira ruins, New Mexico.

Adaption to an agricultural lifestyle.

Farming was probably initially adopted to augment the food obtained from hunting and gathering. However, it tied people to one locality, at least for some of the year. Also, surplus food could be stored for later consumption. Consequently, permanent villages formed, pottery containers were made, tools were developed, storage pit houses built, family routines adjusted to accommodate agriculture, and shamans entered the spirit world to ask for bountiful harvests.

Left: Bandelier National Monument. Right: New Mexico Antiquities graphic.

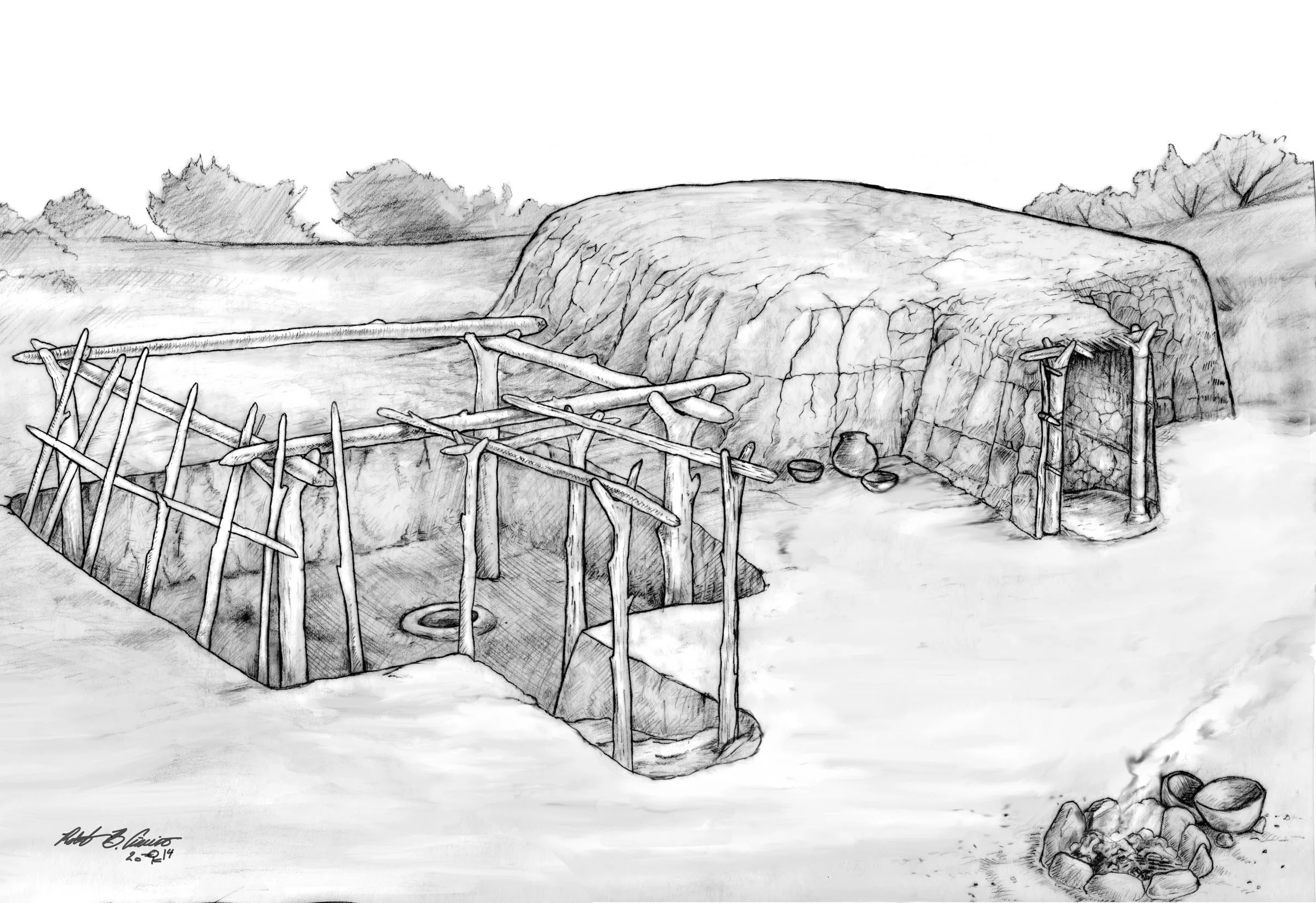

Pit house

By 600-800 CE, Southwest groups were living in villages for most of the year. In the southern Sonoran Desert, square houses were erected in a shallow pit, with the walls and roof constructed using timbers covered with a matting of reeds, grass and earth.

https://desert.com/pithouse-architecture/.

Left: Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico. Right: Graphic from Montezuma Castle, Arizona.

Houses further north were typically subterranean (with floor 4-6 feet below the ground) and roofed with wooden beams, brush, and soil. Entrance was often via a ladder placed in a hole in the roof.

Storage pits were of similar design but smaller.

Kiva

Kivas were also subterranean structures but larger than a house. They were used by the community for group gatherings and religious ceremonies.

The Ancient Pueblo believed their ancestors emerged from a hole in the underworld. Kivas contained a sipapu, a small hole in the floor that symbolized that emergence.

Left & right images: Kivas at Chimney Rock National Monument, Colorado.

Pottery

Ceramics first appear in the Southwest around 200 CE and become widespread by 500 CE.

Pots are fragile and heavy, poorly suited for a mobile, hunting way of life but excellent devices for people in permanent housing. Pots enhanced food preparation by enabling efficient boiling, thereby improving absorption of the nutrients during digestion. Pots were also good vessels for food storage, providing greater resilience against periods of food scarcity.

Pottery technique

Nearly all ancient potters were women. They collected and prepared the clay, then formed the pot by adding ropes of rolled clay onto a molded base. Next, the walls of the vessel were thinned and shaped. The pot was dried in the sun, painted using a brush made from yucca fibers, then placed upside down on a platform and fired using wood and animal dung for fuel.

The Met currently has an exhibit of Pueblo pottery.

Out of my depth

There is a lot written about Southwest pottery and the topic is way beyond the scope of this blog.

Suffice to say that tribal groups evolved their own distinctive pottery styles and ceramic pieces were valued articles of trade. The art was set back in the late 14th century when people dispersed, and populations fell. The arrival of the Spanish virtually ended Indian-to-Indian trade and Southwest pottery reached its lowest point.

The art rebounded in the 19th and 20th centuries and is vibrant today. The pot shown on the right is an example of modern work.

Mimbres Pottery

To reach Gila Cliffs National Monument, we drove up the Mimbres River valley. There was a well-attended harvest festival underway at the rural community’s fairgrounds.

The Mimbres people made red on brown pottery in 700 CE, red on white in 800 CE, Mimbres Boldface in 900 CE and then, in 1,000 CE, Mimbres Classic emerged. Its meticulous black painting on white-slipped bowl interiors made it the most celebrated prehistoric pottery. Mimbres art is clear and representational – exquisite depictions of insects, fish, birds, animals, and humans. (From: Pottery of the Southwest: Allan and Carol Hayes, 2012.)

Towards the end of the 12th century, the Mimbres people dispersed and their unique styles of pottery disappeared.

We visited the Western New Mexico University’s museum in Silver City to view their extensive Mimbres collection. Some of the pieces had a hole in the middle. It was a burial practice of the Mimbres to place a bowl over the face of the dead and peck a “kill hole” in the bottom.

Pueblos, modern and ancient

From the Rio Grande del Norte we moved to Taos and toured Taos Pueblo, home of the Red Willow People.

The original Pueblo, constructed circa 1,325 CE, is a sacred site called “Cornfield Taos.” The Pueblo relocated westward to its current location in 1,400 CE and has been occupied continuously since then.

We enjoyed meeting Pueblo people in their traditional homes and hearing their stories. Trevlyn purchased a few items. Clearly, the Ancient Pueblo did not disappear; the culture is alive and being perpetuated.

Taos Pueblo, New Mexico.

Church history

St. Jerome church was originally constructed in 1619. It was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 against the Spanish and was rebuilt in 1692 when the Spanish returned.

In 1847, during the Mexican-American war, the US Army attacked Taos Pueblo. St. Jerome church and the men, women and children that sought shelter within it were annihilated. The bell tower still stands and the courtyard became a cemetery.

St. Jerome church

An afternoon storm swept over the old bell tower and cemetery, adding to the drama of the place.

Archeologists recognize three primary Southwest cultural divisions – the Hohokam (ancestors of the O’odham), and the Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblo (previously referred to as Anasazi), groups who are ancestors of contemporary Pueblo people.

From Stephen Plog: Ancient People of the American Southwest, 2008.

Changing times

The period from 700-1130 CE was characterized in the Southwest by precipitous change. Population densities increased dramatically, cultures thrived and the countryside was dotted with villages. Large towns like Snaketown and Chaco Canyon supported thousands of people.

Yet, by 1130-1150 CE, many towns and certain areas were entirely abandoned. People dispersed to new areas, thereby shifting the geographical distribution of populations.

Top row, Left: outdoor earth oven. Right: kiva at village.

Bottom row, Left: model of village. Note roof entry to houses. Right: site of village. (All images taken at Bandelier National Monument.)

Gran Quivira village ruins.

Aggregation

During the next 200 years, new large settlements were established, social hierarchies grew, large cooperative efforts were undertaken (for example, Hohokam irrigation canals), conflict increased, and defensive cliff dwellings were built.

Top row, Left: Gila Cliff dwellings, situated adjacent to a spring-fed beautiful canyon creek. Right: Looking down at the canyon from inside a cave dwelling.

2nd row: both images: Ancient homes in Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico.

3rd row: Two views of Montezuma Castle, Arizona showing the buildings and the difficult access to them.

Bottom row, Left: model of house built against a precipitous tuff cliff. Right: back wall of house, showing wall decorations, holes for timber beams, access to cavate (room fashioned out of the rock wall). (Both images from Bandelier National Monument.)

Cavates (rooms carved out of the volcanic tuff), Bandelier National Monument.

Carrizo peak, New Mexico.

The great dispersal

Then, early in the 14th Century, people migrated away, permanently leaving their ancestral homelands. The Southwest again became a sparely populated region.

Mystery

Much has been written on the possible reasons behind the massive prehistoric diaspora.

Climate chaos was probably a major factor. Dating of tree rings indicate mega-droughts, including from 1140 to 1180 CE and 1276 to 1299. These must have been devastating for agricultural communities living in an arid, marginal environment. Ironically, disastrous Salt River floods may have destroyed Hohokam irrigation systems, leading to crop failures and disease.

Other proposed factors include greater aggregation of people into large urban communities (for security, religious & societal reasons), increased hierarchal group structure, deteriorating conditions causing political instability, population densities exceeding the land’s agricultural capacity, depletion of environmental resources in areas surrounding habitation, and increased warfare over diminishing assets.

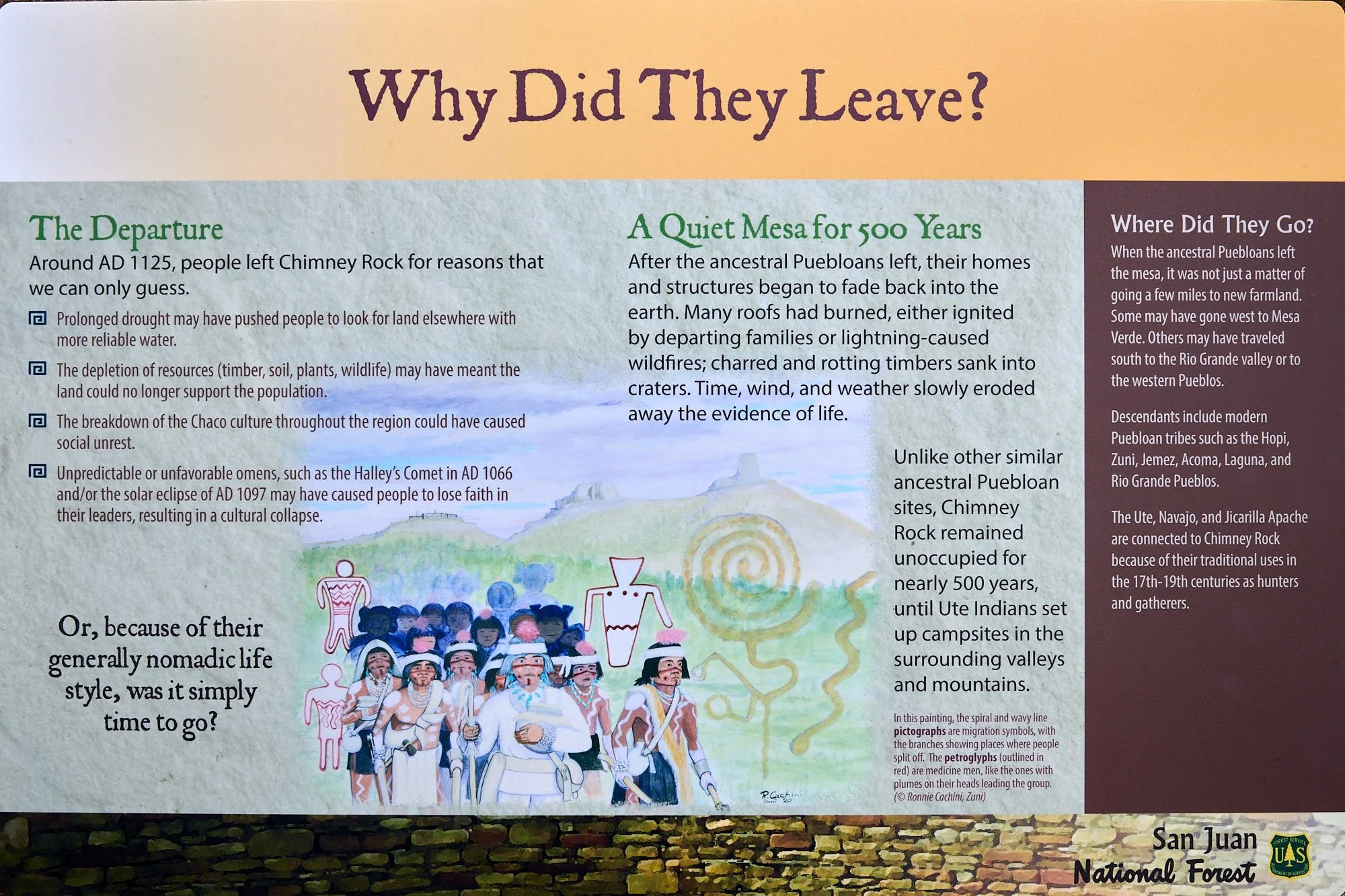

Below are the reasons proposed for the departure of inhabitants from the Chimney Rock complex.

The Ancient Pueblo moved on to new lands when things turned bad. Where can we go when the consequences of climate change intensify?